Harper’s Ferry: Revisiting the Legacies of John Brown and Robert E. Lee

In the dark night of October 16, 1859, abolitionist John Brown and 19 men (14 White and 5 Black) entered Harper’s Ferry, a small town sixty miles NW of Washington, DC where the Shenandoah and Potomac Rivers intersect. They captured a federal arsenal that held thousands of weapons in hopes of freeing nearby slaves and leading an armed insurrection to overthrow slavery.

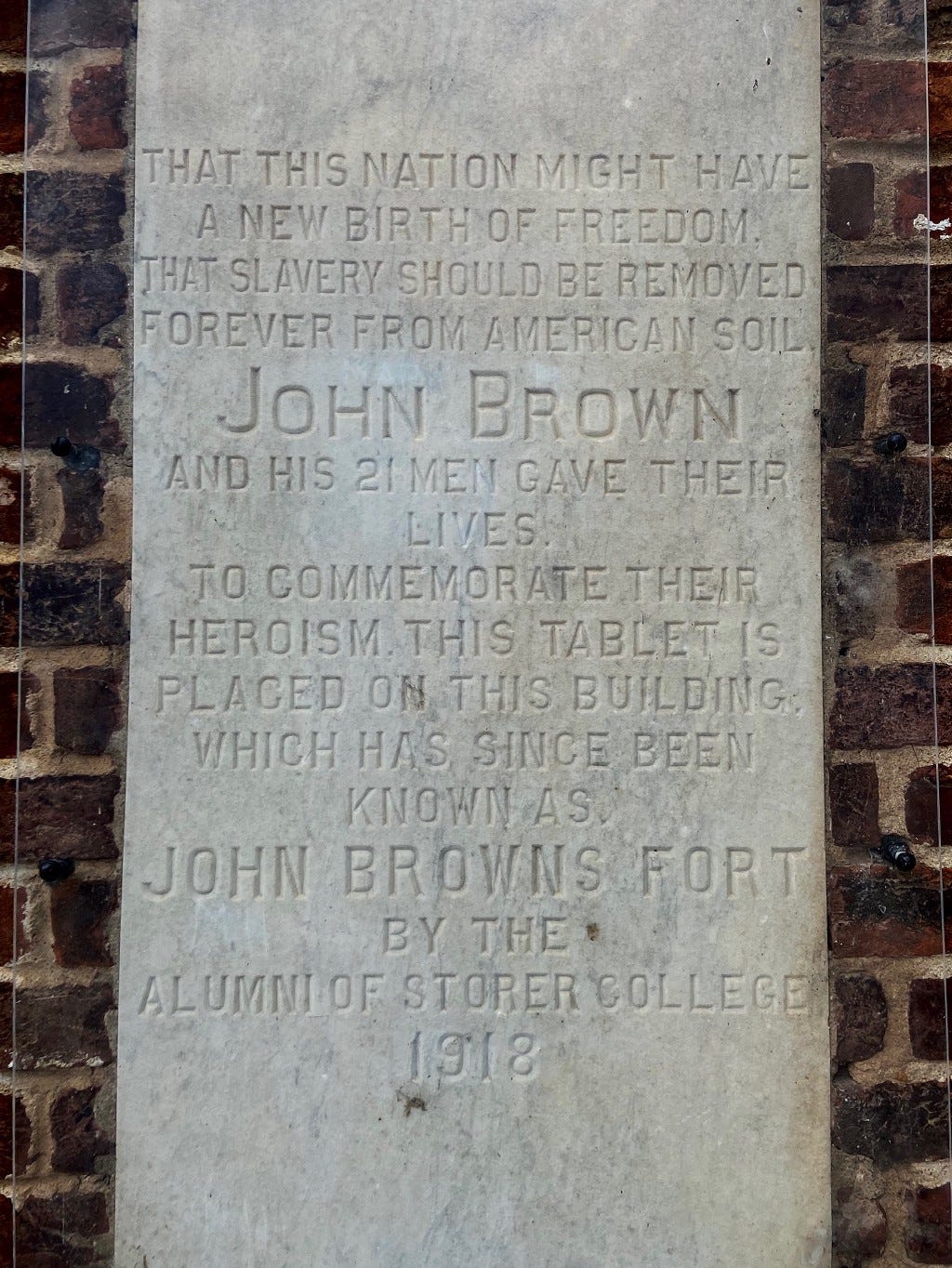

Instead, few slaves joined their cause, and local militias soon surrounded them in the fire engine house, which later became known as “John Brown’s Fort.” They held on for 30 hours until federal troops, under the command of Colonel Robert E. Lee (then of the U.S. Military), overran and captured them. In the end, ten of Brown’s men were killed (including two of his sons), and four townspeople were killed, including the mayor. Brown was seriously wounded. Local officials tried and convicted him and the others of treason within two weeks. They were hanged six weeks later, with Lee in attendance.

Prior to his execution, Brown slipped the guard a paper that read, “I John Brown am now quite certain that the crimes of this guilty land: will never be purged away; but with blood.”

Prophetic words a year and a half before the Civil War’s first shots. Three years later and a mere 18 miles from Harper’s Ferry, Confederate General Robert E. Lee would lead his army into the Battle of Antietam that ended with 22,720 casualties, the bloodiest single day in American military history.

A recent visit to Harper’s Ferry forced me to wrestle with the complexities of Brown’s raid in new ways. On the one hand, he led an attack that murdered innocent Harper’s Ferry residents, including a free Black man while they entered the town. On the other, after watching slavery’s durability through decades of political compromises and negotiations, Brown believed that violence on behalf of those in chains was the only way forward.

Frederick Douglass acknowledged this complexity in an 1881 speech in Harper’s Ferry, saying, “It must be admitted that Brown assumed tremendous responsibility in making war upon the peaceful people of Harper’s Ferry, but it must be remembered also that in his eye a slave-holding community could not be peaceable, but was, in the nature of the case, in one incessant state of war. To him such a community was not more sacred than a band of robbers: it was the right of any one to assault it by day or night. He saw no hope that slavery would ever be abolished by moral or political means.”

As we drove through the rural Maryland countryside in the hours that followed, I imagined John Brown’s willingness as a White man to die alongside his sons for the sake of abolition. He sacrificed the privilege of freedom for the sake of those without freedom. My mind then jumped to Robert E. Lee. He led U.S. forces against Brown and then Confederate Army against U.S. forces several years later.

Both Brown and Lee demonstrated courage, risked their lives, and killed others for their cause — one to end slavery and one to perpetuate it. They also both lost. And yet, when we look at how our society has remembered both men, the difference is stark.

Brown has a smattering of monuments and streets named after him, mostly in places where he fought or lived. Conversely, Lee has countless monuments, streets, schools, parks, and counties named after him, many in places he never stepped foot. His birthday is still state holiday in several Southern states. We wrestle with Robert E. Lee’s contradictions and post-war actions as rationale for these extensive honors, but we narrow John Brown’s life of abolitionism to that one raid to disregard his legacy.

Douglass concluded that same speech with the following, “The South staked all upon getting possession of the Federal Government, and failing to do that, drew the sword of rebellion and thus made her own, and not Brown’s, the lost cause of the century.”