A few weeks ago, our nine-year-old son Hudson came home with a Black History Month assignment to pick a prominent black American and make a case for why he/she should be on a U.S. stamp. His teacher provided a list to help students choose, but Hudson wanted to write about someone not on the list. So, he asked for permission to write about that person. Who was that person?

Robert Smalls.

I was stunned he remembered much about him.

In the throes of virtual work and school in November 2020, my family spent two weeks in Hilton Head, South Carolina as a change of scenery from the four walls of our house. On the last Saturday of the trip, we drove 45 minutes to Beaufort for my wife, Hannah, to meet up with a friend. The day trip excited me because downtown Beaufort also holds the home, church, and gravesite of Robert Smalls, one of the bravest black Americans most people have never heard of. While Hannah and her friend spent time along the waterfront, the kids and I strolled over to check out the sites.

Little did I know that the stories we learned that day would stick with Hudson.

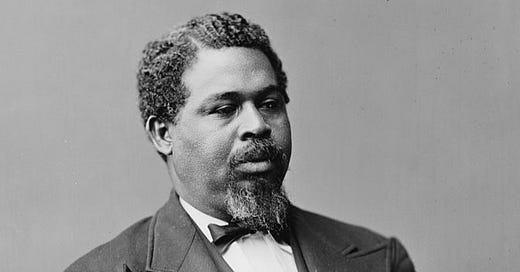

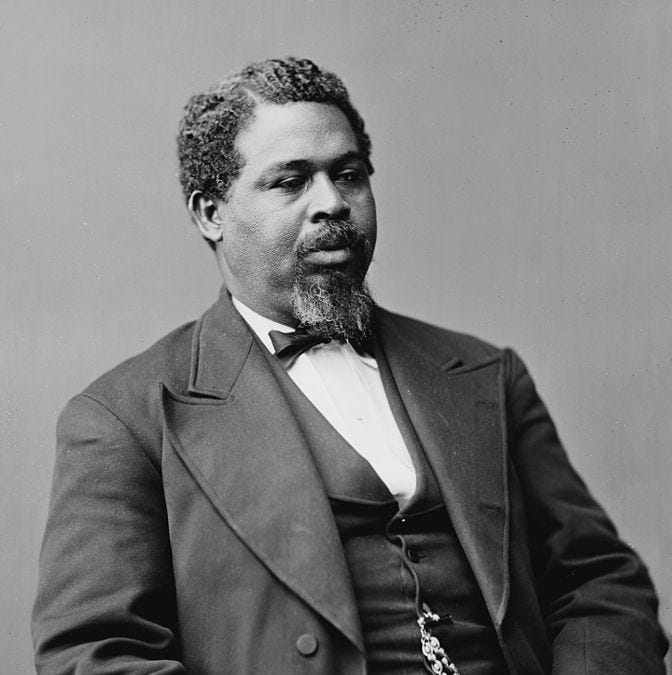

Born a slave in Beaufort in 1839, Robert Smalls’ owner rented him out to work in Charleston as a teenager. During this time, he learned how to drive a boat and navigate the harbor. Once the Civil War broke out, he was placed on the crew of the CSS Planter, a Confederate steamer and gunship. But Smalls had had enough of being a slave.

At 2 AM on May 13, 1862—while the white crew was sleeping on land—Smalls dressed up like the captain, straw hat and all. He and the enslaved crew unmoored, picked up his wife, kids, and a few other slaves, and sailed out of the harbor toward the Union blockade. He knew the whistle signals to get past the Confederate checkpoints. As they escaped past Fort Sumter toward a Union ship, Smalls quickly raised a white flag, just in time to convince Union soldiers not to fire on them.

Upon gaining his freedom, the federal government paid Smalls $1,500 for delivering the CSS Planter, and the Union Army commissioned him as captain of the boat. His knowledge of the South Carolina coastline proved valuable for the Union cause.

As brave as his escape was, he was just getting started. Two years later, while the Planter was in Philadelphia for repairs, a streetcar driver kicked Smalls off his all-white streetcar, despite his status as a Union officer. Since he had time on his hands, he led a mass streetcar boycott that laid the groundwork for Philadelphia’s streetcar integration three years later.

After the war, Smalls returned home to Beaufort. His former owner, like many Southern planters, had fled during the war. Due to back taxes, the local government held the deed. So, using the payout from the CSS Planter and other savings, Smalls paid the back taxes and purchased his former owner’s home—the same home behind which he was born a slave only three decades before.

Soon after, he served as a delegate to the 1868 South Carolina constitutional convention that guaranteed the right to vote to black men, where he also led efforts to enshrine statewide public education in the constitution. Later that year, he won a seat in South Carolina legislature. In 1874, he was elected to the U.S. House, where he would serve five total terms over two stints, fending off voter intimidation and disenfranchisement each time.

In his second race, he was one of a few Republicans to win reelection amid widespread violence against black voters, so the Democratic state legislature trumped up bribery charges against him. Despite eventually gaining a pardon, the scandal, along with widespread voter intimidation, allowed his 1878 opponent, George Tillman, to defeat him. Tillman’s brother, Benjamin, led the Red Shirts, South Carolina’s version of the Klan, that spearheaded violence against black citizens seeking to vote.

Not to be denied, Smalls returned to run against Tillman in 1880, losing again. However, this time he contested the election to the U.S. House citing widespread voter intimidation and violence, hoping the slight Republican majority would rule in his favor. After more than 700 pages of excruciating first-hand testimony, the U.S. House overturned the election 141-to-1 in a vote that all Democratic members boycotted.

Not to be outdone, the South Carolina legislature redrew Congressional districts ahead of the next election, consolidating many of the State’s black voters into one district, pitting Smalls against his ally, Edmund Mackey. Smalls opted out of the race instead of opposing his friend, but Smalls soon returned to Congress via special election when Mackey died during his term. His victory was short-lived, narrowly losing his seat the following year to Democrat William Elliot. Once again, he contested the election with similar extensive evidence of voter suppression, but this time Congress, weary of intervening in Southern elections, refused to overturn the election.

After this loss, he never held elected office again but was appointed to several federal government jobs and played a leadership role in the state Republican Party. One of his final state political acts was serving as a delegate to the 1895 South Carolina constitutional convention, where he fought unsuccessfully to keep white leaders from rewriting the constitution to disenfranchise black voters.

Smalls died in Beaufort in 1915, more than 50 years after his escape.

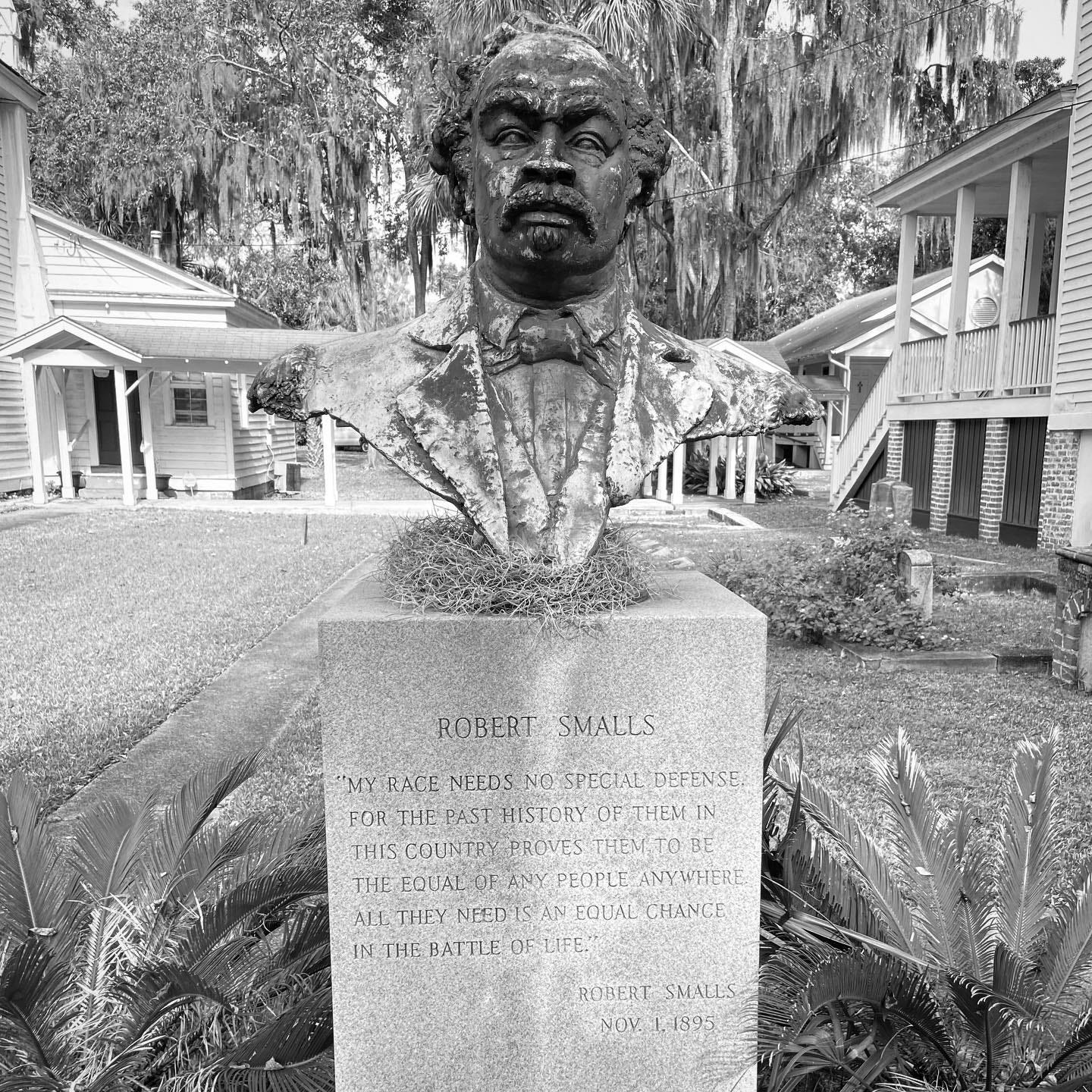

Back to our tour, the kids and I started at Tabernacle Baptist Church two blocks off the waterfront, where Smalls was a member for most of his life and beside which he is buried. A bust stands next to his grave with the following words:

My race needs no special defense. For the past history of them in this country proves them to be equal of any people anywhere. All they need is an equal chance in the battle of life.

Words spoken in 1895, months after he watched white leaders rewrite the state constitution to strip that equal chance.

After a quick detour into a local chocolate shop—I’m not beyond bribery to sweeten the kids’ perceptions of their dad’s history tour—we meandered to Robert Smalls’ home a few blocks away on Prince Street. As we munched on our chocolate bars, we found his two-story, green-shuttered mansion sitting within a fenced-off, well-kept garden. A tall magnolia tree stood guard out front, perhaps planted during his lifetime. It had the aura of coastal antebellum homes owned by South Carolina’s elite.

It’s one thing to read about Smalls buying his master’s mansion, it’s another thing to stand in front of it and picture how that would have played out in the aftermath of the Civil War.

I imagined Smalls sitting in a rocking chair on his front porch, stroking his chin and smiling in contentment as he considered that the home where he had been part of someone else’s generational wealth would become his own family’s generational wealth.

I imagined him arriving home after the 1868 constitutional convention, overflowing with hope that equal rights and education for black South Carolinians had arrived.

I imagined him staring off the porch in disbelief three decades later as he returned home from watching state Democratic leaders strip black citizens of those rights. Owning that house may have been one of his few remaining sources of hope.

I then realized that Robert Smalls died within a year of both my grandfathers’ birth. The past didn’t feel too long ago anymore.

The experience moved me deeply. I shared reflections with my kids, but I wondered whether they would remember anything other than chocolate bars and tired legs. So, when Hudson decided to write about Robert Smalls for his 3rd grade assignment, I welled up with pride and gratitude.

Over the last few weeks as Hudson and I revisited Smalls’ story together, I came to the same conclusion as him—Robert Smalls deserves a U.S. stamp.

Maybe you do too.

For further reading on Robert Smalls, the U.S. House Archives’ biography provides a readable story of his life.

To close, I want to provide a brief update about my series on the Cherokee tribe’s expulsion from Georgia. So far, I’ve published four of six articles. The final two are both still in process. Work and life demands in 2022 haven’t allowed for much writing time, but I still wanted to publish an article in February. I’d already written about Robert Smalls on Facebook in 2020, so the above post came together quickly. Stay tuned for the final two installments on the Cherokee expulsion!