Stumbling upon "the Black Pearl" (Part I)

How a required detour in North Myrtle Beach spotlights Jim Crow-era beach access

Late last December, my wife’s family converged on North Myrtle Beach for our annual holiday gathering. After we checked in at the leasing office near the town center, I typed our rental house’s address, located four miles south along the coast, into Google Maps. Instead of taking us down the beachfront Ocean Boulevard, it routed us back out to the five-lane Highway 17 for the quickest route.

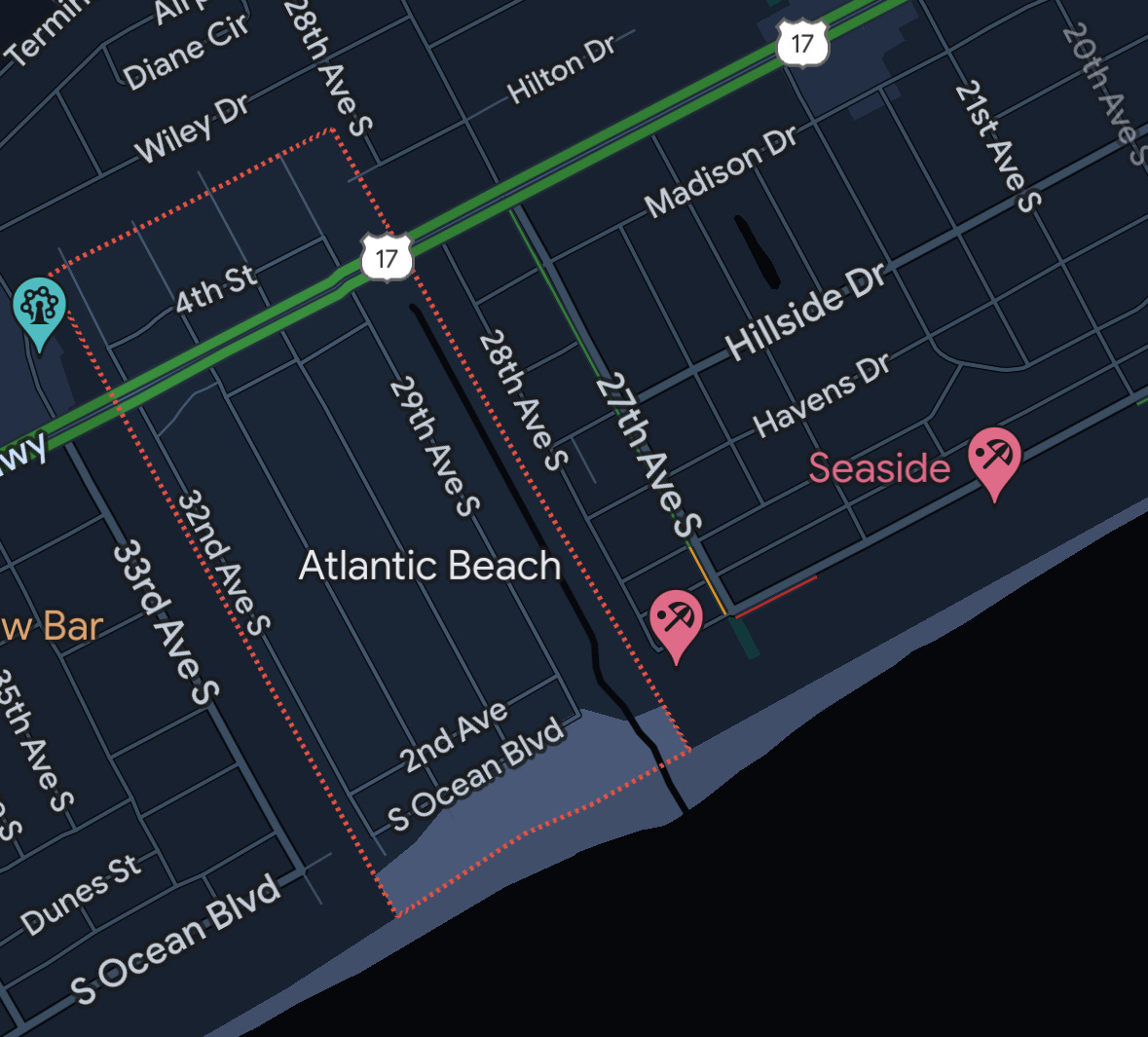

Preferring to hug the coast, I tried to switch to the more direct route but noticed it wasn’t possible. Ocean Boulevard dead-ended for a four-block stretch before picking back up for the rest of North Myrtle Beach. In fact, none of the parallel roads connected on either side of a four-by-seven rectangle of blocks between the beach and Highway 17. Then, I noticed that this carveout was actually a different town—Atlantic Beach. North Myrtle Beach enveloped it on three sides like Pac-Man facing the ocean.

For a second, I wondered why Atlantic Beach was a separate town. There had to be a good story. But it was raining, and the rest of the family was waiting for us to unlock the house. I surrendered my quest for the beachfront route and turned toward Highway 17. My brain soon shifted into “dad-unloading-the-Tetris-packed-van” mode, chasing away my curiosity.

That night, though, Atlantic Beach circled back into my mind. I pulled out my phone to search for the story.

I soon learned that we had stumbled onto what photojournalist Richard Frishman might call a “ghost of segregation”—a vestige of our country’s segregationist past that lingers in our landscapes today.

Atlantic Beach’s other name is “the Black Pearl,” one of the only South Carolina beaches that black Americans could visit during the Jim Crow era. Its continued existence today as an independent municipality is rooted in that past.

In 1934, local ordinances and white-owned private property prevented black people from accessing the beach along the Grand Strand, the sixty-mile stretch of South Carolina beaches along present-day Myrtle Beach. To change that, George W. Tyson, a black entrepreneur from the nearby town of Conway, purchased 47 acres of beachfront land. Soon after, he founded the Black Hawk Night Club as an entertainment venue and subdivided lots for other black professionals to purchase. Eight years later, he purchased another 49 acres and formed the Atlantic Beach Company with ten shareholders, drawing from local black physicians, educators, and business leaders.

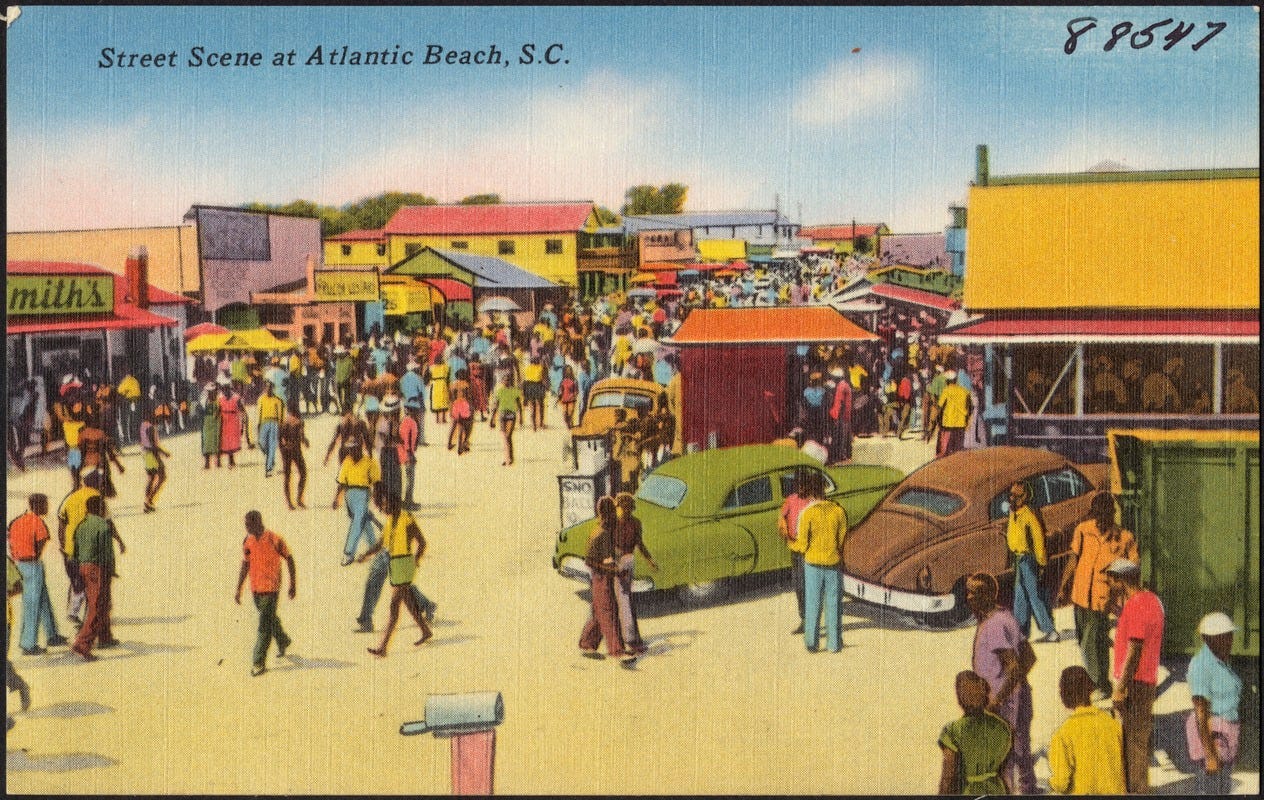

Throughout the 1940s and early 1950s, Atlantic Beach boomed with hotels, restaurants, clubs, rental houses, and other businesses as it became a mecca for black locals and visitors across the Eastern seaboard. Black entertainers like James Brown and Fats Domino stayed there when in town to perform at white Myrtle Beach clubs, sometimes performing in Atlantic Beach clubs after they finished their other gigs.

To maintain separation, local white leaders constructed fences on either side of Atlantic Beach to prevent black beachgoers from venturing into neighboring beaches.

Atlantic Beach’s fortunes began to turn in 1954 when Hurricane Hazel slammed the Carolinas as a Category 4 storm with an 18-foot storm surge, destroying 80 percent of the beachfront structures along the Grand Strand. It decimated Atlantic Beach’s pier, two hotels, and most wooden structures. Many owners didn’t have insurance or significant savings, so they struggled to rebuild.

In much of the Grand Strand, real estate developers capitalized on depressed beachfront property values to purchase properties in bulk for hotels and other commercial developments. Atlantic Beach owners held onto their land—losing it would also mean losing access to the beach.

In 1968, the municipalities surrounding Atlantic Beach—Cherry Grove, Ocean Drive Beach, Crescent Beach, and Windy Hill—consolidated into the town of North Myrtle Beach to share services and coordinate development. Against the backdrop of racist exclusion and white resistance to desegregation, Atlantic Beach’s leaders turned down the invitation to join North Myrtle Beach, retaining autonomy but also responsibility for public services and infrastructure.

This decision coincided with the federal government's stricter enforcement of desegregation in the late 1960s, which enabled black people to venture onto other beaches and stay in recently developed hotels that were previously off-limits. Few white people did the opposite.

Still struggling to recover from Hazel and no longer a monopoly for black beachgoers, Atlantic Beach declined, much like black business districts across the country—an unfortunate side effect of integration.

In the 1980s, Atlantic Beach had 800 year-round residents. Recent Census estimates place its population now hovering around 300. As its population has decreased, its poverty rate has crept upward to nearly 50%. Although it is packed annually for Memorial Day weekend’s Black Bike Week, it’s a shadow of its former mystique the rest of the year.

The next afternoon, my 11-year-old son, Hudson, and I walked up the beach to explore Atlantic Beach. As we trudged through the cold December sand, we talked about how we never second-guessed the right to visit the beach. Nearly every summer since my childhood, I’ve spent a week at Folly Beach near Charleston. Growing up, it never occurred to me that, just a few decades before, white Americans landlocked black Americans from visiting the beach. In fact, Folly Beach had a reputation for roughing up black locals who defied its segregation order. I didn’t want Hudson to take beach access for granted like I had.

After fifteen minutes, the relentless line of beachfront high rises and hotels came to a football field-length pause.

We had reached Atlantic Beach.

Thank you for reading Southbound. Next week in Part II of this series, we’ll explore what Hudson and I learned on our walk through Atlantic Beach. Then, we’ll dig into the town’s current dispute about its future, which turns out to be the latest chapter in a decades-long debate that has instead mired it in the past.

If you liked this article, please click the ♥️ icon at the bottom of this post, leave a comment, or forward it to a friend. Doing so provides me with helpful feedback and helps others find the article.

Very interesting and provocative! Thanks, Sam, for continuing to uncover history that is just as important for us as adults as for children like Hudson.

A few years ago I had a conversation with a black woman who was in high school in 1968. After she shared what it was like to have the curtain pulled back and new opportunities open up, she talked about how it also marked the beginning of the end for so many once-thriving black businesses and neighborhoods—that it’s a very painful thing people still don’t want to talk about.