A NICU Fourth of July

How watching fireworks from an unexpected location spurred gratitude for our country

Fireworks peaked over the hospital building standing between us and the city’s annual display. Most exploded below our sightline—only faint yellow and red flashes escaped to reflect off the clouds above. The popping that usually forces kids to plug their ears whispered through the thick glass, no match for the incessant beeping of NICU heart monitors in our 11th-floor room. And yet, this muted expression of a Fourth of July tradition provided a new source of gratitude for our country.

Independence Day was the epicenter of my childhood summers. My parents hosted an annual celebration for family and friends at my grandmother’s house that featured a children’s parade, yard games, and a picnic. My grandmother shared a driveway with several other homes between Valley Drive and Highway 41 in downtown Dalton, creating an ideal parade route.

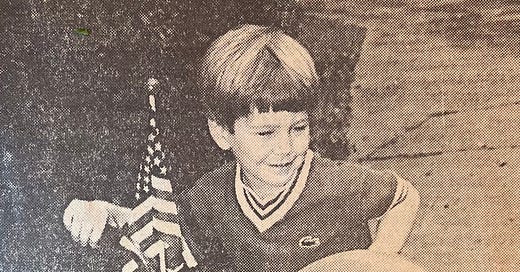

Kids showed up well before parade time to decorate their wheeled vehicles with red, white, and blue streamers, balloons, flags, and other patriotic regalia (mine even made the local paper in 1989).

Participating parents had one peculiar requirement: wearing a hat. Violators were dispatched to my parents’ dreaded hat basket, a pile of tacky hats that spent the rest of the year in our basement closet. They might return with a faded Goofy hat, a brimmed women’s hat with rumpled silk flowers, or a green foam Statue of Liberty visor. Some relished this fate each year; others never made the mistake twice.

My dad queued up an instrumental version of John Philip Sousa’s The Stars and Stripes Forever on the cassette player to signal the parade’s beginning. Kids set out to make a loop around the plastic stop sign at the end of the driveway while their parents cheered them on. Older kids zoomed back and forth, showing off their bike-riding prowess by popping a wheelie on the driveway’s speed bump. The youngest participants crept forward with three-inch steps in their plastic cars.

After the parade, families and friends teamed up for a three-legged race, an egg toss, and a sack race (in real nylon potato sacks that also spent the rest of the year in the closet next to the crazy hat basket). Bragging rights were on the line. Once winners were crowned, families pulled out their picnics, ate watermelon, and later jumped in the pool to cool off.

That evening, we made our annual pilgrimage to the hill above the Dalton Parks & Recreation Department, gearing up for fireworks as Lee Greenwood’s God Bless the USA blared through the speakers next to the softball field. Back then, fireworks were illegal in Georgia, so the town’s display was the only show in town, except for those who smuggled them in from those monstrous fireworks stores on the Georgia-Tennessee border (as if they wouldn’t blow their cover upon the first explosion).

After the show, we’d return home long past bedtime, worn out but filled with pride for our country.

These experiences, among others, inculcated a happy, carefree patriotism that lasted into adulthood. But, as I learned about and wrestled with the ugly elements of our nation’s past in the years that followed, my unbridled love of country waned. On a few occasions, that journey threatened to snuff out all enthusiasm.

In recent years, I’ve landed on an equilibrium, of sorts, aiming for a patriotism that loves our country enough to celebrate its strengths, confront its shortcomings, and build toward a future where we live up to our founding ideals (I wrote more about this sentiment last fall). Still, I haven’t quite figured out what celebrating the Fourth of July should look like from this new posture.

On June 23, our third child, Luke, was born. Unlike the first two, Luke is entering our family through adoption. Hannah and I drove through the night to Florida after the adoption agency called late in the afternoon on June 22 to let us know that he was on the way. We’ve been here ever since.

Luke arrived a few weeks early, weighing in at three-and-a-half pounds. He was also born with an extra copy of his 21st chromosome, also known as Down syndrome, and carries a heart condition that will require surgery in a few months (common among children with Down syndrome). He is progressing well, but all these factors mean that we’re holed up at the NICU for much of the summer.

Hannah and I spend most of our days taking turns holding him for long stretches and feeding him every three hours, soaking up as many cuddles as we can (our other two kids are still back home with family). We also wash our hands 267 times a day and have gained an unexpected knack for untangling wires and tubes that make the back of our TV back home look tame.

Days in the NICU bleed together. They bring a new kind of fatigue born not from physical activity but from the constant tracking of heart monitors and his latest medical updates.

In one sense, the Fourth of July was just like most other days here, except for Luke’s hospital-provided patriotic onesie and my reading of several articles on my phone (I recommend these by Esau McCaulley and Tom Nichols). Since our room faces the direction of the city’s fireworks display, we ordered UberEats and planned to enjoy Luke’s first fireworks together.

I hadn’t planned to write anything.

As we watched the obstructed fireworks show, I found myself caught up with gratitude. I felt thankful that he was born in a hospital with the latest technology and a highly-training medical staff. Without that, Luke may not be alive.

I felt thankful that his Down syndrome diagnosis hasn’t downgraded the level of care he is receiving, as would have been the case for most of our nation’s past and is still the case in some places even today. Without that, Luke may not be alive.

Then, I thought about what we see each day as we enter and exit the hospital—a steady stream of moms and babies from all races and income levels being discharged—riding off in Teslas, Odysseys, and Corollas—to start new lives. I felt thankful that none of us fear missile attacks, supply shortages, or preventable diseases.

I thought about how the medical staff, security guards, cafeteria chefs, new parents, and families we see every day probably span the spectrum of political views and life experiences. The broader world says we can’t coexist. And yet, in a hospital where sustaining the lives of women and babies takes center stage, those disagreements fade to the background as we root for each other’s progress.

It wasn’t always this way, as I explored in my last article about the 1931 death of Fisk University’s Juliette Derricotte in my hometown. And, gaps in healthcare outcomes and access still persist in many places. But spending these weeks at the hospital has provided me with an unexpected sense of optimism and—dare I say—pride in this country.

Since most of us aren’t faced with existential threats to our well-being on a daily basis, we have the privilege to fight about important but secondary issues, painting an illusion that we are more divided than we actually are. But in moments of need, like the birth of a new child into the world, I’m thankful that we can still come together around the common goal of human dignity.

Maybe sitting in that gratitude is an appropriate way to celebrate the Fourth of July.

Thank you for reading Southbound. I’d love to hear from you. Please post your reflections below or send me a message. If you think others would benefit from reading this article, please forward or share it on social media. Personal recommendations are the most common way others learn about Southbound.

Thanks for your thoughtful article. I have found with my husband's health challenges that friends and family are supporting and we are recipients of acts of kindness more often than before.

Praying for you, Luke, Hannah and your 3 at home with family each night.

Q

Amen,Sam, AMEN!