“Jule made a different woman of me. I was a bigoted young Kentuckian when we first knew each other, but I couldn’t with any self-respect remain that kind of a person working by the side of her.”1

That’s how Gladys Bryson described her 34-year-old former co-worker, Juliette Derricotte, after her death from injuries in a 1931 car accident. For nearly a decade, Juliette, a black woman who grew up in Athens, Georgia, traveled to colleges across the United States with the Young Women’s Christian Association (YWCA), promoting a vision of interracial cooperation rooted in helping students see each other’s humanity.

Prominent black leaders like Langston Hughes and W.E.B. Du Bois mourned her death. Dr. Howard Thurman, a Morehouse professor and future mentor to Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., preached at her funeral, reminding the grieving attendees, “This is an unfinished world; she leaves an unfinished task, who shall take it up? Driven by the power of her spirit we dedicate ourselves anew to the process within this imperfect world.”2

The real tragedy, though, wasn’t the car accident. It’s that Juliette wasn’t taken to the white-only hospital a mile and a half from the accident. Instead, Juliette and fellow passenger, Nina Johnson, received care in a doctor’s office and then a black woman’s home—both walking distance from the hospital—for eight hours before two ambulances transported them to a black hospital 25 miles away. Nina died on the way; Juliette died the next day.

When I first learned this story, I grieved the role that racism played in her death. But, the grief cut more deeply because of where the car accident occurred—on Highway 41 just outside Dalton, Georgia, my hometown. The hospital where Juliette and Nina weren’t taken, Hamilton Memorial Hospital, is where I was born. It’s where my mom was born too. It’s where I cried through seven stitches in my left eyebrow after my brother pegged me with a baseball in our side yard. It’s where numerous family members and friends have received life-saving treatment. I wondered, how could Juliette and Nina’s race have prevented them from receiving the same level of care?

Born in 1897 as the fifth of nine children in Athens, Juliette Derricotte grew up within walking distance of the University of Georgia, then a white-only institution. Her mother, Laura, had light skin, sometimes even passing as white. Her father, Ike, was born enslaved just before the Civil War. His owner, Stevens Thomas, hailed from one of Athens’ founding families. Thomas’ plantation home is now the Phi Kappa Tau fraternity house on campus.

As a child, Juliette dreamed of attending the Lucy Cobb Institute, a prestigious, all-girls private school a few blocks away. Founded just before the Civil War by Thomas R.R. Cobb—the brother of Confederate Major General Howell Cobb I I wrote about in the Battle of Columbus earlier this year—the school admitted only white girls.

Although she couldn’t attend, Juliette didn’t allow this barrier to inhibit her dreams. After finishing high school, she attended Talladega College, a black Christian college in Alabama. Upon graduation in 1918, she enrolled in the YWCA’s training program in New York City and soon received a job as secretary of the YWCA’s National Student Council, traveling to university chapters across the country to train them on developing and maintaining healthy organizational structures.

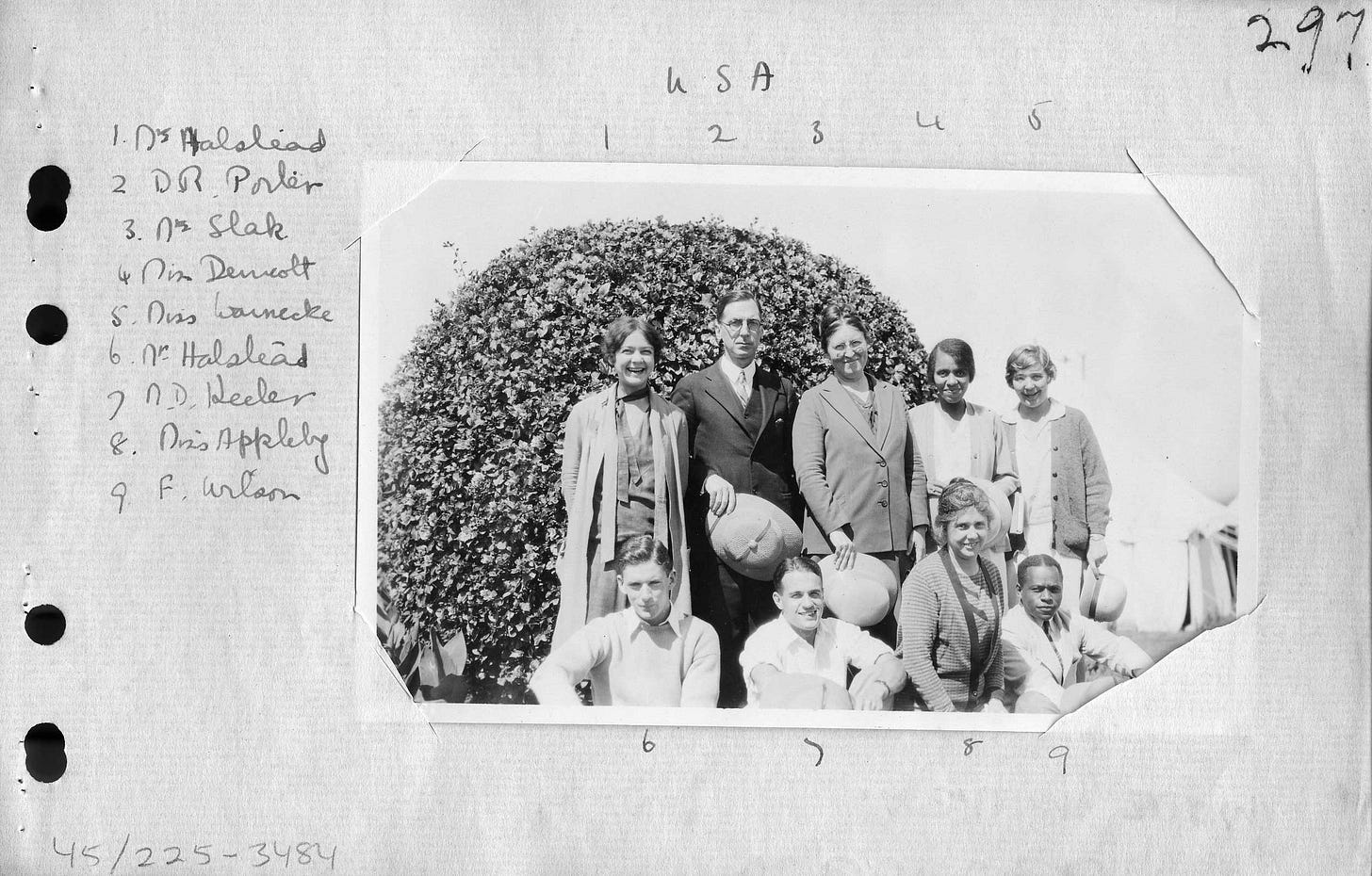

In 1924, her peers nominated her as a YWCA delegate to the World Student Christian Federation’s conference in London, a seven-week meeting of hundreds of delegates from around the world every four years. The conference was a turning point for Juliette as she worked alongside and befriended delegates from across the world. Experiencing how they could unify around a common mission despite their racial, ethnic, and national differences changed her.

After the trip, her visits to campus chapters shifted beyond organizational nuts and bolts—she taught students how to bridge racial barriers by seeing each other as people with inherent worth. At one institution, several white students called off an upcoming KKK rally after hearing her speak.

Amidst this work, she joined the first graduate chapter of the Delta Sigma Theta sorority in New York and earned a master’s degree in religious education from Columbia University. In 1928, once again she represented the YWCA at the World Student Christian Federation conference, this time in Southern India. She traveled through Europe, across the Mediterranean, and then through Red Sea en route to the conference before returning through China and across the Pacific Ocean—a rare opportunity for any recent college graduate at the time, much less the daughter of a former slave who lived much of her life in the Jim Crow South.

Months later, Juliette reflected on her trip in W.E.B. DuBois’ magazine, the Crisis, saying:

With all the differences and difficulties, with all the entanglements of international attitudes and policies, with all the bitterness and prejudice and hatred that are true between any two or more of these countries, you are here friends working, thinking, playing, living together in the finest sort of fellowship, fulfilling the dream of the World’s Student Christian Federation ‘That All May Be One.’3

Now in her early 30s and energized by experiences of intercultural cooperation, no one would have blamed her for staying away from the South, an infertile place for interracial harmony. Instead, the plight of Southern black women burdened her. She resigned from the YWCA to accept a role as Dean of Women at Fisk University, a prominent black Christian university in Nashville. Amidst the transition, she became the first female trustee of her alma mater, Talladega College, and was named to the YWCA board.

Although Fisk served only black students, its faculty had been all white until not long before she arrived. Her experiences abroad and with YWCA chapters made her a bridge between white faculty and newly hired black faculty, many of whom were new to the South.

Two years into her role, Juliette skipped a November Fisk football game to visit her parents in Athens for the weekend. In an era when black travel through the South was inconvenient and risky, she invited three Fisk students—Nina Johnson, Edward Davis, and Miriam Price—to join her on the trip in her Ford Model A.

They never made it to Athens.

The four stopped for a late lunch in Chattanooga with a black couple, the Trimbles, before setting out on Highway 41 South for the rest of their November 6, 1931 trip to Athens. Around 4 pm and a mile and a half outside of Dalton, a Ford Model T sedan crossed the center line and hit Juliette’s Ford Model A, flipping her car and throwing Juliette and Nina from it. The impact knocked Nina unconscious and left Juliette moaning in agony on the grass. Edward and Miriam escaped with non-life-threatening injuries. The white driver of the other car yelled at them before fleeing the scene.

A woman who lived nearby and a man from out of town drove them into town for medical care. Not knowing where black people could receive treatment, they flagged down locals to ask. Edward retells their efforts to find treatment:

The man took us into Dalton. We were near the center of the town when he asked a number of people where the hospital was. A few did not know; others said there was no hospital for Negroes; and others said they would have to take us to some doctor’s home. He drove on farther and asked a white boy about a hospital or a doctor. The boy told us his father was a doctor and lived right up the street. He took us to his home. This doctor’s name was Dr. Broaderick.4

Dr. Broaderick, along with two other doctors—Drs. Steed and Shellhorse—treated them in their offices on King Street, a mere two blocks from Hamilton Memorial Hospital.

From Dr. Broaderick’s office, Miriam called the Trimbles—the black Chattanooga family they met for lunch earlier in the day—and a Fisk University official to let them know of the accident. Upon hearing the news, Mr. Trimble called for two Chattanooga ambulances to drive to Dalton, while a group of four Fisk administrators and faculty members jumped in their car to reach Juliette and Nina as soon as possible.

After examination, the doctors were concerned about Nina and Juliette’s chances of survival. However, instead of requesting admittance to the hospital, they moved Juliette and Nina to the home of a local black woman, Alice Wilson, on nearby Emery Street. Wilson’s home served as a makeshift infirmary, or “colored sanitorium,” where black residents often received minor surgeries or stayed when they needed multi-day care. Miriam and Edward would later describe the home as dirty and lacking medical supplies. But at the time, it was all Dalton’s black residents had.

Nina and Juliette were placed on a folding bed and a couch where they would lie for more than five hours until ambulances arrived just after midnight. They were taken to Walden Hospital—Chattanooga’s black hospital that lacked modern equipment—rather than the more updated Erlanger Hospital nearby, even though it had a segregated wing.

Nina died on the way, having never regained consciousness. Juliette was admitted and spent the next 18 hours in and out of lucidness, complaining of severe pain in her midsection. In addition to Miriam and Edward, Ethel Gilbert, a white Fisk official and Juliette’s close friend who traveled down from Nashville after the accident, remained with her. Juliette died the next evening, November 7.

Her family held her funeral at First AME Church in Athens two days later. She is buried in nearby Gospel Pilgrim Cemetery.

Immediately after Juliette’s death, Ethel Gilbert returned to Dalton to interview locals and investigate what happened. As a white woman, she hoped to get more straightforward answers from locals on what happened. Her interview notes provide the backbone of the story told above. Four days after the accident, she summarized her findings in a letter to the YWCA leadership, saying:

If anybody makes a report that says in effect ‘everything that could be done was done,’ it merely means that everything that could be done for Negroes was done. . . . I shall always have to compare in my mind all of the things that were done that would not have been done to me if I had been injured. I shall always have to remember that within one half hour after the accident, I would have been in a modern hospital.5

As I read the eyewitness accounts from Ethel’s investigation, an interesting pattern emerged—the white residents who encountered Juliette weren’t openly racist. In fact, most did what they thought they could do to help. For example, Dr. Steed bemoaned the lack of a black hospital wing but never questioned why it’s absence should prevent life-saving care. When Ethel pressed him on why he didn’t advocate for hospital admission given the severity of her condition, he responded matter-of-factly, “Oh no’m. We don’t take ‘em there.”6

When Hamilton Memorial Hospital opened in response to the 1918 flu pandemic, its founding leaders didn’t provide access for black residents. White residents didn’t question or challenge that decision. Just like the rest of the South, white superiority and racial separation were embedded in all aspects of life. Thus, when two black women needed life-saving medical care a decade later, cultural norms and hospital rules placed race-tainted boundaries around their compassion. Doctors and onlookers were nice and tried to help, but their curtailed view of human dignity short-circuited their definition of help.

Juliette had helped many white people overcome that curtailed view, at least until the day her car landed in a ditch. Though her conversations and speeches over the prior decade had invited many to question white supremacy, her moans and pleas for help that day didn’t unsettle Dalton residents’ commitment to it. Maintaining racial separation was more important than saving lives.

We’ll never know if Juliette or Nina would have survived had they been taken to Hamilton Memorial. Certainly, their odds would have been higher. Perhaps, more tragically, we’ll never know how many black Dalton residents suffered or died due to the lack of adequate medical care. More broadly, we know that the lack of quality healthcare access for black Americans caused worse health outcomes, such as increased rates of premature death, heart disease, and infant mortality. Though these gaps have narrowed since the Jim Crow era, racial disparities in healthcare access and outcomes still persist today, even when controlling for factors like income and education level.

When we look back at the Jim Crow era, murders and lynchings often dominate our attention. It’s easy to condemn a Klansman in a white hood or a lone assassin of a civil rights leader. It’s much harder to wrestle with deaths like Juliette and Nina’s because we have to confront the well-intentioned white people whose complicity in the system enabled their suffering.

My grandfather, Tom Jones, was a 15-year-old high school student when the car accident occurred. His family lived on the corner Highway 41 and Emery Street, four blocks from Alice Wilson’s “colored sanitorium.” Did he know what happened to Juliette and Nina? Did he and his parents—my great grandparents—know about the lack of quality medical care available for Dalton’s black residents? Did they care?

I’ll never know the answers to those questions. But what I can do is search my own life to find where I take the status quo for granted, where, regardless of my motives, my assumptions blind me from seeing injustice around me. Maybe you can do the same.

Thank you for reading Southbound. I’m indebted to Curtis Rivers, the director of the Emery Center, Dalton’s African-American history museum, where I first learned about Juliette’s story four years ago. He has answered my many questions with patience and generosity. The Emery Center is located across the street from where Alice Wilson’s home once stood.

I’d love to hear from you. Please post your reflections below or send me a message. If you think others would benefit from reading this article, please forward or share it on social media. Personal recommendations are the most common way others learn about Southbound.

In a future article, we’ll return to Dalton for another chapter in the town’s health care journey. Juliette and Nina’s deaths represent a low point for health care in Dalton, but a high point came 25 years later when Hamilton Memorial Hospital moved to a new, expanded hospital—incidentally a mile and a half outside of downtown on Highway 41 just like the site of Juliette’s car accident. When the new building opened in 1956, it did so as one of the first desegregated hospitals in the South, six years before Grady Hospital in Atlanta.

How did that happen? What was the community’s response?

That’s our story for next time.

Letter from Gladys Bryson to Laura Derricotte, November 15, 1931. Accessed in Geiger, Roger L., Gasman, Marybeth. Higher Education for African Americans Before the Civil Rights Era, 1900-1964. United Kingdom: Transaction Publishers, 2012.

Wygal, Winifred. “Juliette Derricotte: Her Character and Her Martyrdom,” The Crisis, March 1932 edition. Available here.

Ibid.

Ethel Bedient Gilbert. Letter to Leslie Blanchard, Executive National Student Council YWCA. November 10, 1931

Ibid.

Share this post