Giving A.L. McCamy the Memorial Service He Deserved

The last recorded lynching victim in my hometown will finally receive a marked grave, 88 years and a day after his murder.

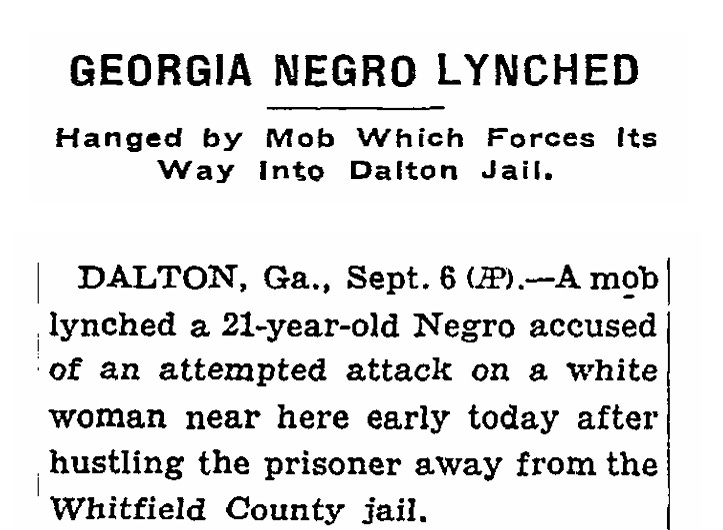

At 1:30 a.m. on Sunday morning, September 6, 1936, a 150-man mob gathered outside the Whitfield County jail in Dalton, Georgia, my hometown. Several minutes later, its leaders entered the jail in search of a prisoner. Their target: Alonzo “Lon” McCamy, Jr, a 21-year-old local black man.

They grabbed the keys from the lone jailer, 59-year-old John Pitts, and seized McCamy from his cell. As they exited, McCamy purportedly broke free and ran through a vacant lot between the jail and Emery Street School, the local school for black children.

He didn’t make it far. Members of the mob opened fire, and McCamy fell to the ground as several bullets pierced him. Though McCamy likely died from the gunshots, his anti-climactic demise didn’t quell the mob’s hunger for vengeance. Witnesses reported that they tied him behind a car and dragged his body to a rock crusher site across town on Tibbs Road, a few hundred yards south of where Civitan Park’s playground sits today. Once there, they hung his body from a telephone pole and riddled it with more bullets. Whitfield County Sheriff J.T. Bryant found his body four hours later in a nearby ditch.

You might be asking, what did Lon McCamy do?

Several nights earlier, a prominent local white widow, Eva McCamy (no relation to Lon), awakened to a man standing in her bedroom. When she screamed, the man fled. While she couldn’t identify the entrant, several local men claimed to have seen Lon McCamy, who worked as her yardman, nearby around that time. Despite an alibi that he was with his girlfriend at the time, deputies arrested him without a warrant. McCamy had a prior arrest record, so his guilt was assumed.

Despite widespread rumors of plans for an attempted lynching on Saturday night, Sheriff Bryant made no preparations. He only left one jailer on duty and went to sleep in his jail quarters that night. When interviewed afterward, Bryant said he was only awakened by the gunshots outside the jail, and that the mob disbursed so quickly that he didn’t have time to arrest or identify any of its participants.

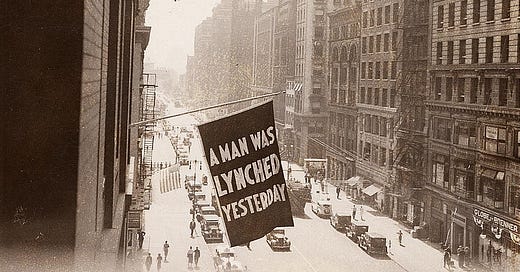

Bryant’s investigation into McCamy’s murder was short-lived. In the next circuit court term, local judge C.C. Pittman urged a grand jury to investigate the lynching, but no arrests were ever made. Local newspapers scarcely mentioned it beyond alluding to gossip. Though local media remained quiet, McCamy’s lynching made national headlines in the New York Times and the Atlanta Daily World, among others. The NAACP also hung its “A Man Was Lynched Yesterday” flag outside its 5th Avenue New York City headquarters.

Despite growing up in Dalton, I didn’t learn about Lon McCamy’s lynching until well after I left town for college.

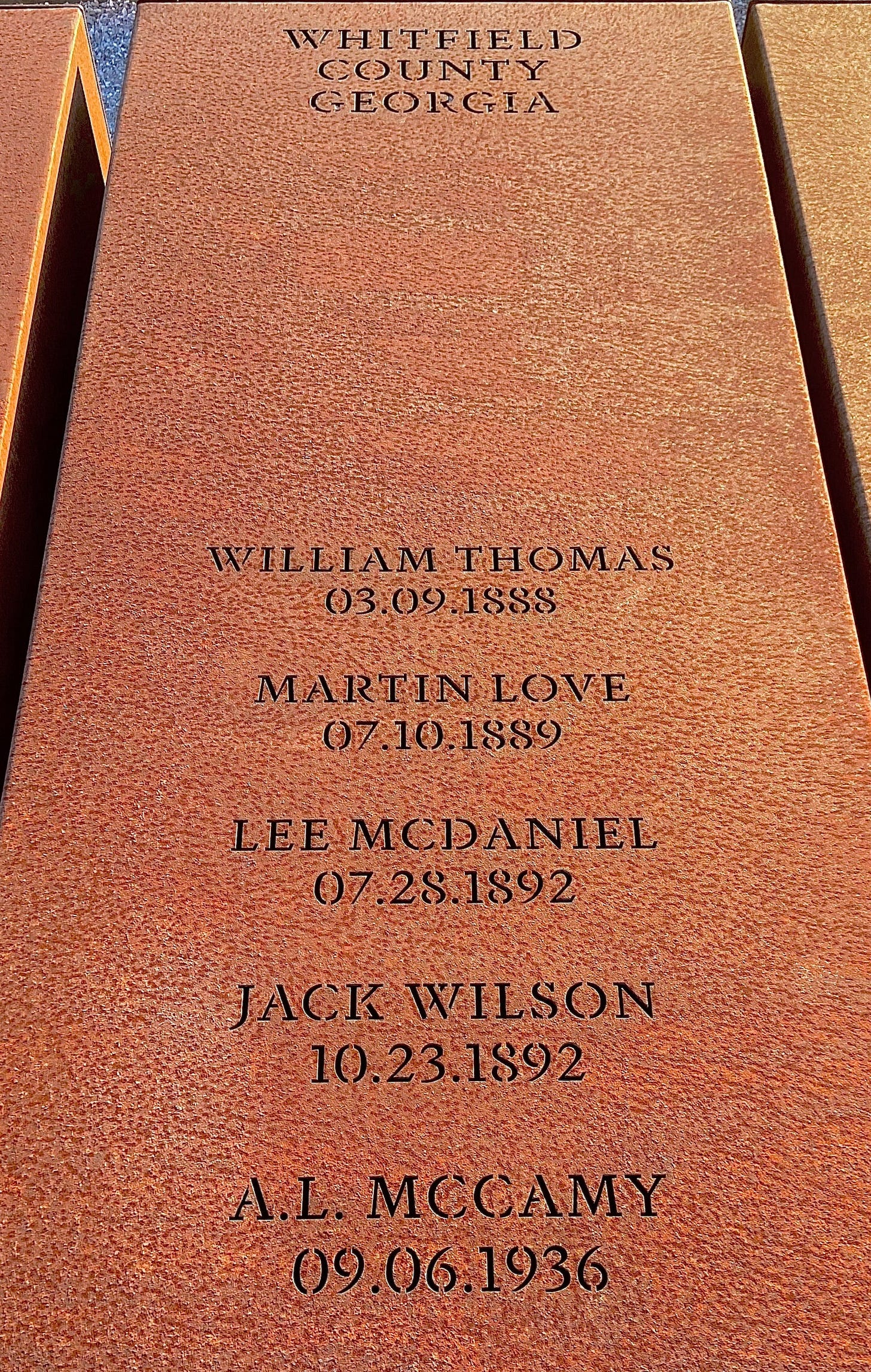

On a cold January day in 2020, my family stopped at the National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery on the way back from a family funeral in Louisiana. Opened two years prior, the memorial seeks to acknowledge and mourn the thousands of racial lynchings that happened during the Jim Crow era.

While I had expected to grieve our country’s past as we walked through the six-acre memorial, I wasn’t ready to find the names of five lynching victims inscribed underneath “Whitfield County Georgia” on one of 800 rusty steel blocks suspended from the ceiling, each representing an American county where a lynching occurred.

My stomach turned as I wrestled with why I had never heard of these men or their stories. I wrote about my reflections on the visit in Dalton’s newspaper, the Daily Citizen, several weeks later.

In the months that followed, I scoured local newspaper articles published in the days following each lynching, read history books, and asked locals to recount their memories.1 One story—Jack Wilson’s—jumped to life because its aftermath differed from most Jim Crow-era lynchings, not to mention that I discovered my great-great grandfather’s name in newspaper articles about it.

This research transformed me and ultimately led me to publish his story, The Lynching of Jack Wilson and Why It Matters Today, in October 2020. Its publication coincided with the national groundswell of concern about racial injustice and healing after the killings of Ahmaud Arbery, George Floyd, and Breonna Taylor.

That moment felt like we were on the precipice of a breakthrough—where widespread awareness of racial violence would lead to a consensus around the need to collectively grieve that past and hold substantive conversations about how to move forward.

That precipice instead served as a peak. Pandemic-driven isolation, social media algorithms, tribal purity tests, and loud voices on the extremes conspired to deform concerns about racism into bitter debates over “wokeness,” critical race theory, and DEI. On the right, initial openness among many to engage and understand racism past and present soon morphed into skepticism of indoctrination or exaggeration. On the left, those who raised concerns about the more radical aspects of critical theory or identity politics were labeled as racist.2

Openness to nuance and good faith engagement suffered. The constant verbal warfare left people on edge, mistrusting anyone perceived to be on the other side. Some are fatigued or exasperated by continued conversations about race. Others are demoralized as they have watched once promising openness evaporate. Still, others have tuned it all out.

In short, the energy to continue learning about racism and wrestle with why it matters today has evaporated.

While the broader momentum waned, a small group of multiracial current and former Dalton residents created the Whitfield Remembrance Project to promote community awareness and remembrance of victims of racial violence. I’m grateful that they invited me to join them, even though my participation has been limited while we navigated the birth and adoption process of our son, Luke.

With the support and resources of the Equal Justice Initiative, which built the National Memorial for Peace and Justice, we launched the Whitfield County Racial Justice Essay Contest in September 2023, awarding more than $5,000 in scholarships to five local high school students last spring.

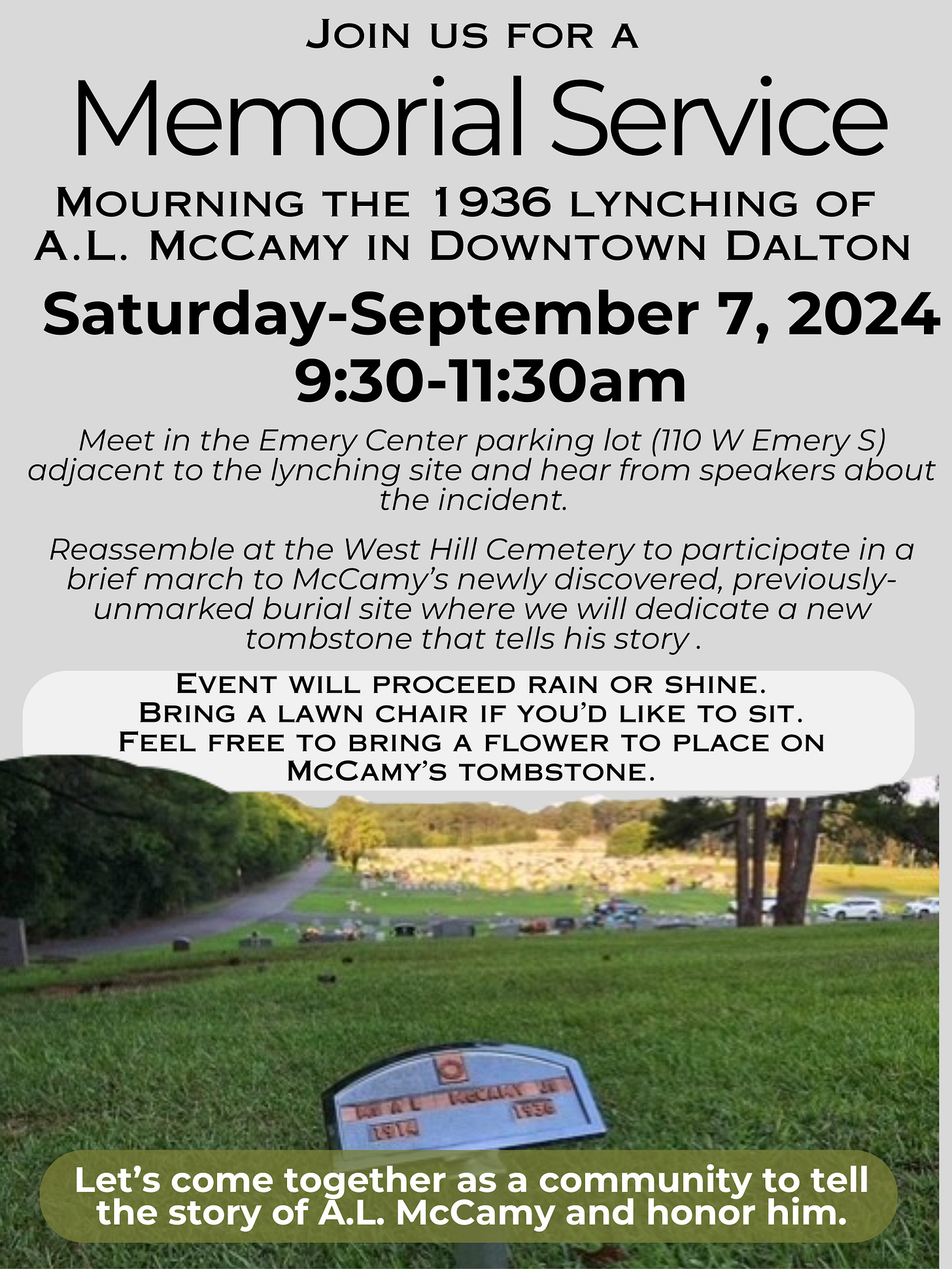

That led us to the next step in building community awareness: a public memorial service for one of the victims, which will be held on Saturday, September 7, 2024, 88 years and a day after Lon McCamy’s lynching off Hamilton Street in downtown Dalton.

At 9:30 that morning, we’ll gather for the memorial service behind the Emery Center, Dalton’s African American history center, which also happens to be adjacent to where Lon McCamy was shot.

After the ceremony, we’ll drive to West Hill Cemetery, where McCamy is buried in a recently rediscovered, unmarked grave. We’ll dedicate a permanent tombstone that tells his story (the image below is a temporary marker placed a few weeks ago).

Public grieving of Lon McCamy’s lynching can’t bring him back, nor can a dedicated tombstone. But it can spotlight a past that has existed under the surface for too long—for black folks, as whispers of fear and anguish, and for white folks, as if it never happened. And, in doing so, perhaps it can remind us of our common humanity, of the importance of public lament in the healing process, and of the necessity to wrestle with a complete picture of our country’s past as we push to live up to its ideals, regardless of our partisan leanings.

In his book, Prophetic Lament, author and pastor Soong-Chan Rah writes:

There has been a deep and tragic loss in the American story because we have not acknowledged the reality of death. Stories remain untold or ignored in our quest to ‘get over’ it. But, in the end, we have lost an important part of who we are as a nation and as a church. We have yet to engage in a proper funeral dirge for our tainted racial history and continue to deny the deep spiritual stronghold of a nation that sought to justify slavery. . . . Racial reconciliation requires the truth telling of the funeral dirge lament and the expression of grief (p. 50).

May Lon McCamy’s memorial service be a down payment in that process in Dalton. If you’re local, I hope you’ll join us.

Thank you for reading Southbound. If you liked this article, please click the ♥️ icon at the bottom of this post, leave a comment, or forward it to a friend. Doing so provides me with helpful feedback and helps others find the article.

If you plan to attend Lon McCamy’s memorial, please let me know. I’d love to connect with you there!

Learning Lon McCamy’s story didn’t require extensive research like the others—local attorney Sam Gowin published his story in 2017. Most of the details in the opening section of this article are drawn from his careful research from primary sources.

I recognize that this description of the last few years is overly simplistic. It’s not intended to be exhaustive or litigate one side or the other. Instead, the goal is to point out that what first appeared to be promising and necessary conversations about race didn’t yield progress, and in many ways, our national discourse on race is worse off than prior to 2020.

Sam, thank you for your article. I am a member of the group, which has evolved into Whitfield Remembrance Project, and I look forward to meeting you in person on September 7. Sincerely, Dick Neelly

Great article, especially regarding the complacency and lassitude that has re-emerged around issues of racial justice due to extremism on both ends of the political divide.