Why Do Most Georgia Rivers Still Have Native American Names?

My process to find the answer pushed me to reflect on how places get named and why that matters today.

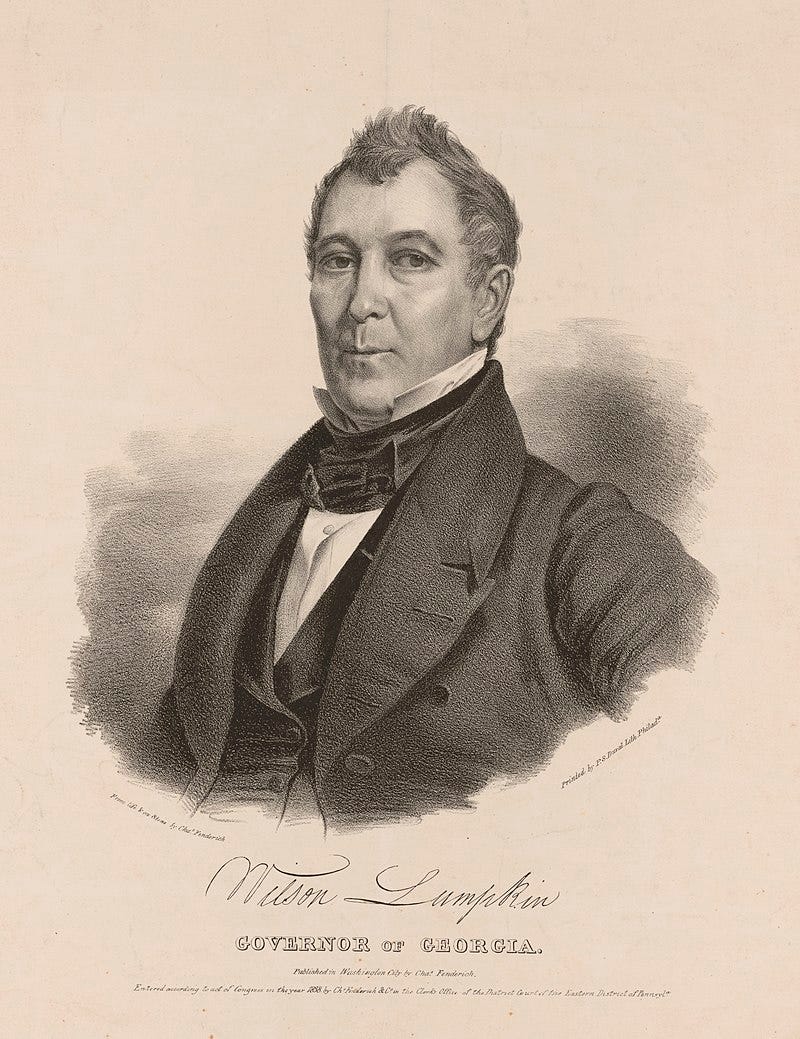

Back in December, I explored how counties in former Cherokee land were named for men who played pivotal roles in deporting the tribe, including Gilmer, Lumpkin, Forsyth, and Cobb Counties. Amidst that journey, I also noticed how most rivers and creeks in that same land still have Native American names today. This realization made me wonder: why did rivers keep their names amidst the naming and renaming that occurred around them? And, more generally, why do we name places? What do those names say about our values?

When I stepped back to take a broader look at Northwest Georgia place names, it struck me how many places have names with Cherokee or Muscogee roots, sometimes right next to places named for men who kicked them out. For example, the county seat of Lumpkin County—named for the Georgia governor who ignored the U.S. Supreme Court’s ruling to protect Cherokee sovereignty—is Dahlonega, which comes from the Cherokee word for yellow, dalonige’i. Fitting name for the epicenter of Georgia’s gold rush that also accelerated Cherokee deportation.

Prior to Cherokee expulsion, the Chattahoochee and Chestatee Rivers served as borders between Cherokee land and the State of Georgia. The Oostanaula, Etowah, Coosawattee, Coosa, and Conasauga Rivers today weave between cities and counties created and named during or after Cherokee expulsion. Georgia leaders could have easily renamed rivers too, but they didn’t. As they erased tribes from the land, why didn’t they erase tribal names from that land too?

To answer that question, I needed to step back to reflect on why names exist in the first place, something I’d never really thought about.

Cultures throughout history have depended on names to help them find places, demonstrate connections between family lineages and land, or commemorate people and events. The United States is no different. Historian George Stewart’s 1940’s book, Names in the Land, provides an exhaustive picture of American place names.

Prior to European arrival, Native Americans used names as “sign-posts, noting something permanent and easily recognized, something to distinguish one place from other places—size, or shape, or color, or the kind of rocks or trees found there” (6). Then, as a tribe lived in a certain area for some time, they shifted to naming places after memories or events that happened.

Dr. Katrina Phillip, a Native American historian and citizen of the Red Cliff Band of Lake Superior Ojibwe, writes:

“The idea of place—what it means, what it’s called, and by whom—is integral to how we position ourselves, literally and figuratively, in a particular space. It’s how we define our relationship to a place, how we claim ownership or knowledge. To be from somewhere is to claim and be claimed. Names of cities, towns, lakes, rivers, and mountains hold stories and histories of people, of journeys, of violence. . . . The acts of naming, of renaming, of reclaiming, underscore these contested complexities.”

Rivers were central to Native American life. They served as highways, sources of food, barriers to cross, and destinations for game trails. Thus, tribes often named rivers first, although they rarely named the entire river the same name throughout its course.

As Europeans arrived, naming took on an additional purpose: staking claim to the land. Stewart continues,

“Anything they could do to bolster the legality of their settlement would be useful. Sovereignty of uninhabited or un-Christian lands was generally held to rest upon discovery, and the language of the names of a region was often cited as proof of discovery by that nation” (72-73).

As the British pushed out other European nations, the prevalence of Spanish and French names decreased, except in areas like Louisiana (French) and Florida (Spanish) where other nations had a stronger foothold. Though the American Revolution created a new nation, few citizens advocated for renaming places to rid them of their colonial past. If it did happen, renaming in this era typically reflected “a new enthusiasm rather than an old hatred” (Stewart, 202). Instead, they focused on naming the many new towns, counties, territories, and states formed as settlers moved westward.

Surveyors were often among the first to trek into the new land. They set boundaries between territories and sketched maps with rivers, streams, and mountains that guided settlers and facilitated land claims. Those landmarks needed names, and surveyors, especially those with indigenous interpreters or guides, were more likely to use an indigenous name than create a new one. But, the written name in English often differed from the actual indigenous words. Stewart writes:

“The Europeans constantly made mistakes about Indian names, in form, and in application. They thought in terms of kingdoms and provinces, and failed to realize that Indians thought in terms of tribes. They assumed that a river or a lake had the same name everywhere. They failed to conceive the vast differences between languages of near-by tribes” (10).

He later continues, “at best the English form of a name was only a doubtful replica of what the Indian name had been, and often the one was hardly recognizable to the other” (Stewart, 108).

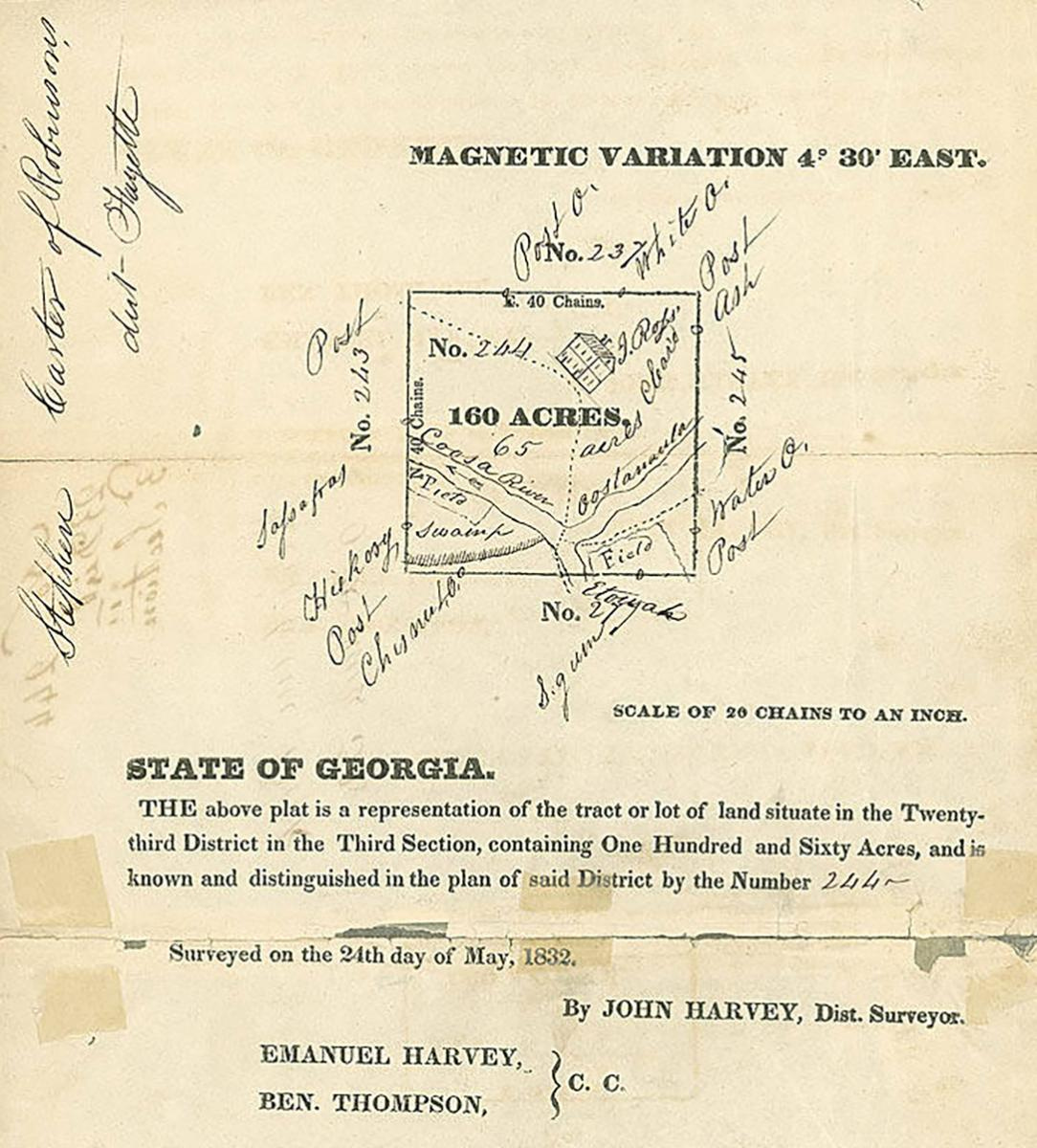

In Georgia’s case, the state legislature sent surveyors into Cherokee land to prepare for land lotteries as soon as it became clear that the federal government under President Andrew Jackson wouldn’t stop them. To see if this happened in Georgia, I tracked down the 1831 survey map shown below that carved Cherokee land up into numbered regions. It follows the same pattern as elsewhere in the country—most named places are natural landmarks or small Cherokee towns that haven’t survived. Nearly all rivers carry Native American names, as seen in the second, more zoomed-in map.

As state leaders distributed lots, they used those same maps when assigning land titles, hardening these indigenous-sounding names into legal documentation well before the new owners arrived to evict the Cherokee from “their” land. As such, any attempts to change names faced a cumbersome process that may have proved not worth the effort. Ironically, then, it may have been the centrality of private property in white American settler culture that preserved indigenous names of rivers and creeks—landmarks the tribes viewed as communal sources of life.

While this may explain the persistence of indigenous names on natural landmarks, it still begs the question of why Americans still used indigenous names for new towns and counties. Sometimes the intent was to honor the tribes who used to live there, especially if enough time had passed where bloody conflicts were distant memories. In other cases, an indigenous name added a mystique or perceived connectedness to nature intended to grab the attention of potential residents. In either case, it often had limited connection to names that Native Americans actually used. Stewart writes

“The great majority of our present Indian names of towns are thus not really indigenous. Far even from being old, they are likely to be recent. . . . Troy or LaFayette is likely to be an older name in most states than Powhatan or Hiawatha. The romantics of the mid-century and after applied such names, not the explorers or frontiersmen” (Stewart, 279). (Author note: by mid-century, he is referring to mid-1800s)

In sum, as new generations had only distant memories of Native Americans, indigenous-sounding names served as painless memorials to a tragic past or charming allures to attract new residents.

With that backdrop in mind, I needed to consider one final angle: what place names say about the givers of those names. If you think about it, a place’s name reflects more of the values of the people who named it than the person or event for which it was named. Tribes valued unspoiled nature and communal, intergenerational storytelling, so they named places with descriptive words or as a way remember something that happened there—places like Elatse’yi (“green place”) or Agista’ti’yi (“where they stayed up all night”). Rarely were places named after people.

In contrast, white settlers valued development, progress (as they defined it) and individual achievement, so they often named the fruits of their efforts—towns and counties—after military or political leaders who helped establish them, like Wilson Lumpkin, John C. Calhoun, John Forsyth, and Francis Bartow. Others were nostalgic for European homelands (Dublin) or ancient empires (Rome).

To those settlers, rivers were vehicles for development and convenient boundaries, rather than resources to be stewarded and honored. They were a means to an end. In a strange way then, rivers may have retained their indigenous names not just because they were included in early maps but also because settlers viewed them as a lower priority than land development and ownership. Thus, it may be poetic justice that the place names we have today actually point to what both the Cherokees and the state’s early leaders valued most.

It's in that context that we must stop and ask ourselves: what do we value most today?

This article is the fifth in a series of articles about Cherokee expulsion from Georgia. In a few weeks, I’ll be back to wrestle with how we should approach naming today. Specifically, what should we do about places named after people who don’t embody our values now?

After that, I’ll conclude this series with a final article on what this season of reflecting on Cherokee expulsion from Georgia has taught me and how it has helped me see the world through a different lens.

If you think others would enjoy reading along too, please forward this email or share via social media.

Very interesting and thorough piece. Always wondered how names were chosen. When we see names like places like Nashville and Franklin overused in multiple states, or a Brentwood - I seldom wondered why the lack of originality. But when it comes to Georgia and Florida and Louisiana - it was unique. Now it makes sense.