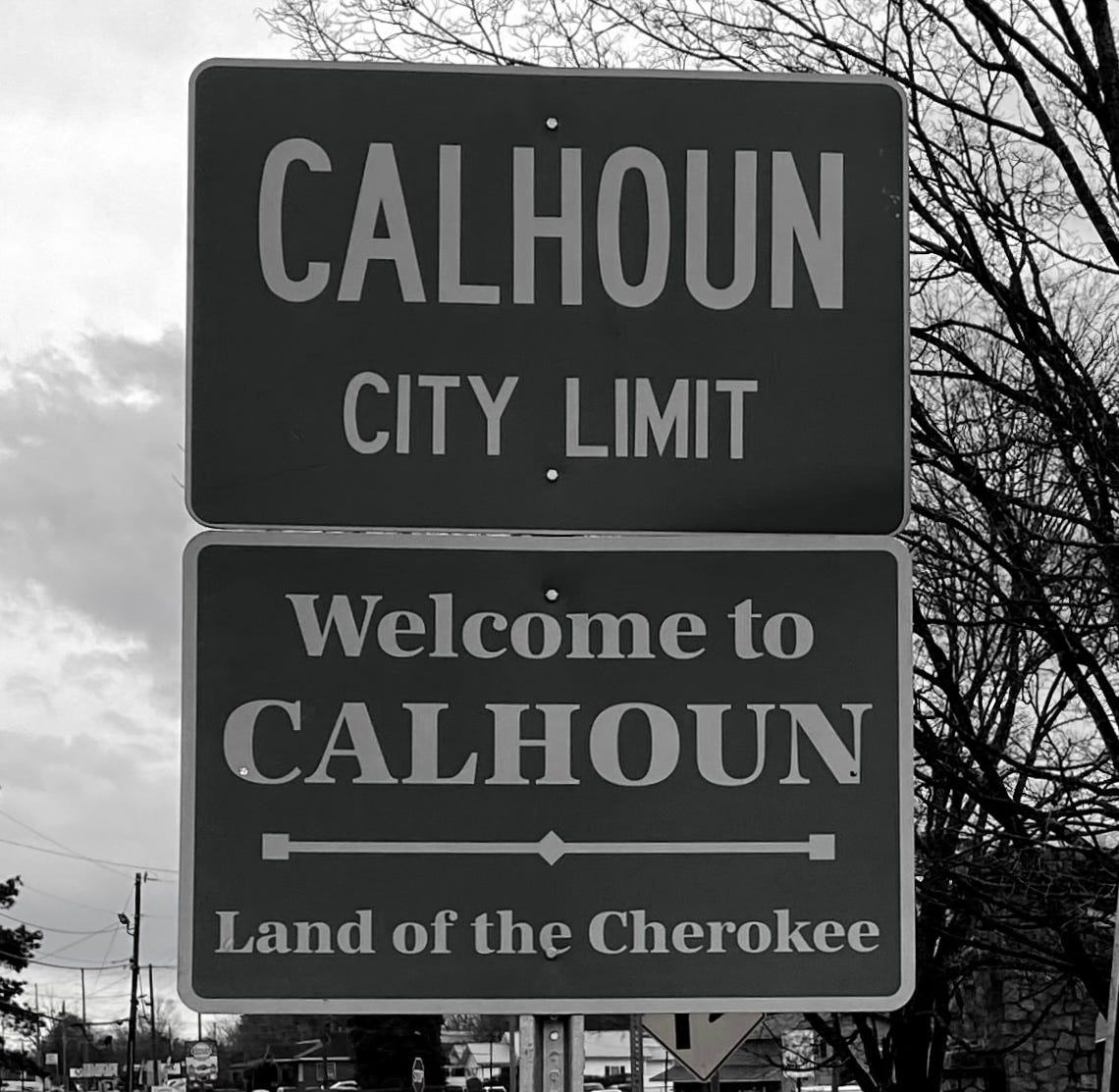

Welcome to Calhoun | Land of the Cherokee?

A look at how cities and counties in Cherokee territory were named. Part IV of a seven-article series on Cherokee deportation from Georgia.

Wilson Lumpkin. Lumpkin County.

George Gilmer. Gilmer County.

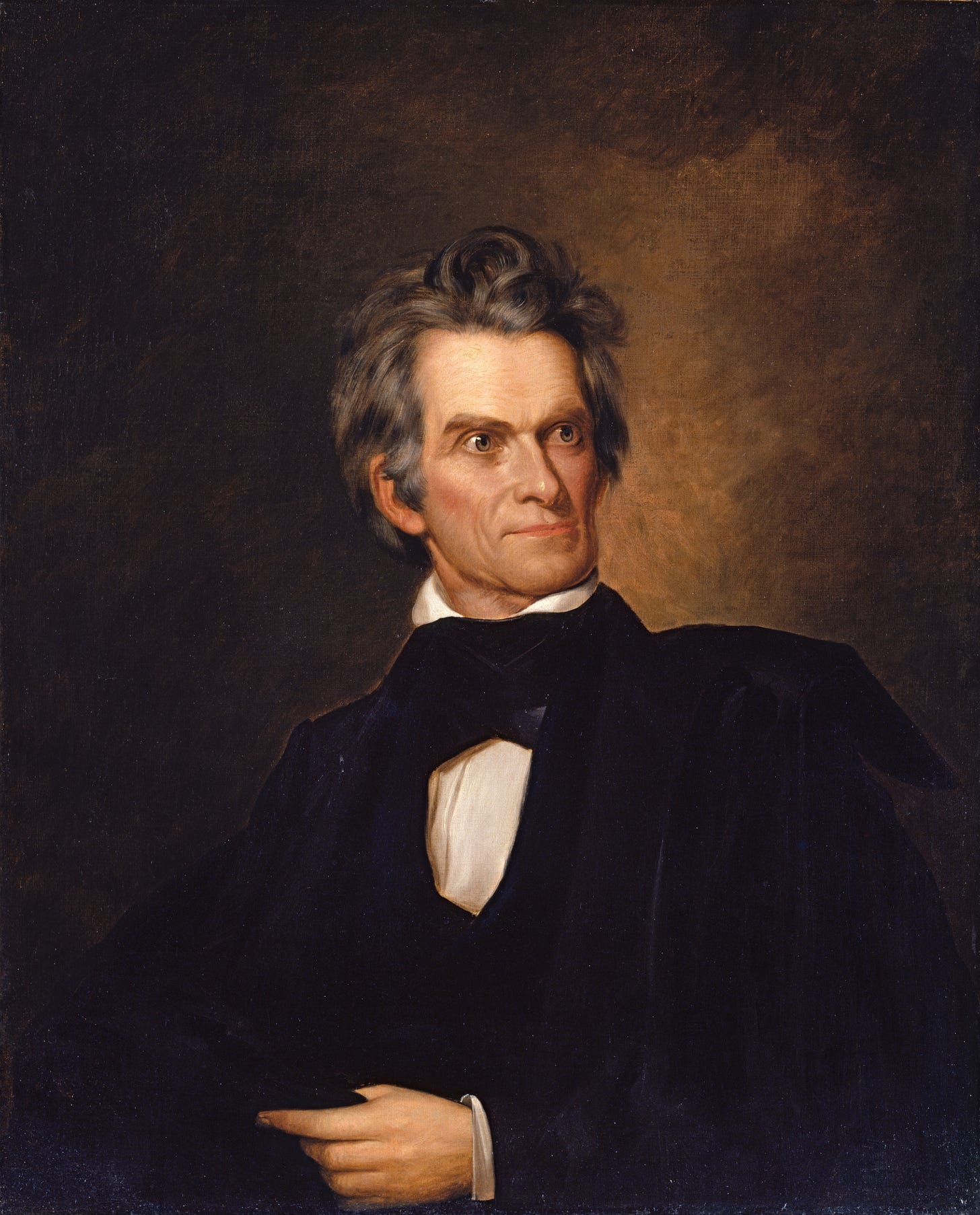

John C. Calhoun. Town of Calhoun.

Over the last year as I learned the stories behind the Cherokee Nation’s expulsion from Georgia, I noticed how several cities and counties in Cherokee territory were named after men who played leading roles in their deportation. I began to wonder whether the roles these men played in that effort motivated state legislators to name North Georgia cities and counties after them. Today’s article digs into my journey to answer this question.

To begin, I circled back to the events immediately following the tribe’s 1838 deportation to Oklahoma. As mentioned in the last Southbound article, even as the Cherokees were still being held in the stockade a few hundred yards from New Echota, settlers wasted no time moving onto the land. The new owners broke down New Echota’s buildings and converted the town back into farmland. Like the Cherokee, New Echota soon disappeared from Georgia.

At that time, the nearest Georgia town was Dawsonville (different from the present-day town by the same name), located in Cherokee territory four miles southwest of New Echota.1 White Georgians founded it in 1828 as an outpost in their efforts force out the tribe. In 1850, just 12 years after the Trail of Tears, the Georgia legislature renamed it “Calhoun” in honor of the recently deceased former U.S. Vice President and long-time South Carolina Senator John C. Calhoun. That same year the legislature redrew counties and named Calhoun the county seat in the newly created Gordon County, named for William Washington Gordon, a former Savannah mayor who had been President of the Central Railroad and Banking Corporation before his death in 1842.

At first glance, these names seemed unrelated to New Echota or the Cherokees. And, the legislative acts that named them say nothing about intent. So, I wondered—what would a prominent South Carolina politician and a coastal mayor have to do with a city and county in Northwest Georgia?

More than you might think.

Let’s start with John C. Calhoun. He is most known as an unabashed supporter of slavery and states’ rights. Unknown to me, though, was his role as a long-time champion for “Indian Removal.” In fact, he was the first federal official to develop a formal plan for their removal while he was Secretary of War under President James Monroe. In 1819, he served as the U.S. signatory on treaties that ceded Cherokee land in South Carolina and Tennessee to the government. Then, in 1835 when the U.S. Senate voted to approve the Treaty of New Echota by one vote, Senator John C. Calhoun cast one of those votes.

On top of his political role, Calhoun also had a gold-tinted personal stake in Cherokee expulsion. In 1828, a settler named Benjamin Parks became the first white man to discover gold on land bordering Cherokee territory 75 miles east of New Echota, kicking off the Dahlonega Gold Rush. Parks leased the land to find more gold but soon became frustrated by the lack of further discoveries. The property’s owner then sold it to a local judge, who turned around and sold it to sitting U.S. Vice President John C. Calhoun. With his significant wealth, Calhoun set up a mining operation on the land. As thousands of settlers poured into the area and pressed into Cherokee territory, the Calhoun mine became one of the most profitable in the Gold Rush.2

So, Calhoun’s connection to the area is clear. What about William Washington Gordon?

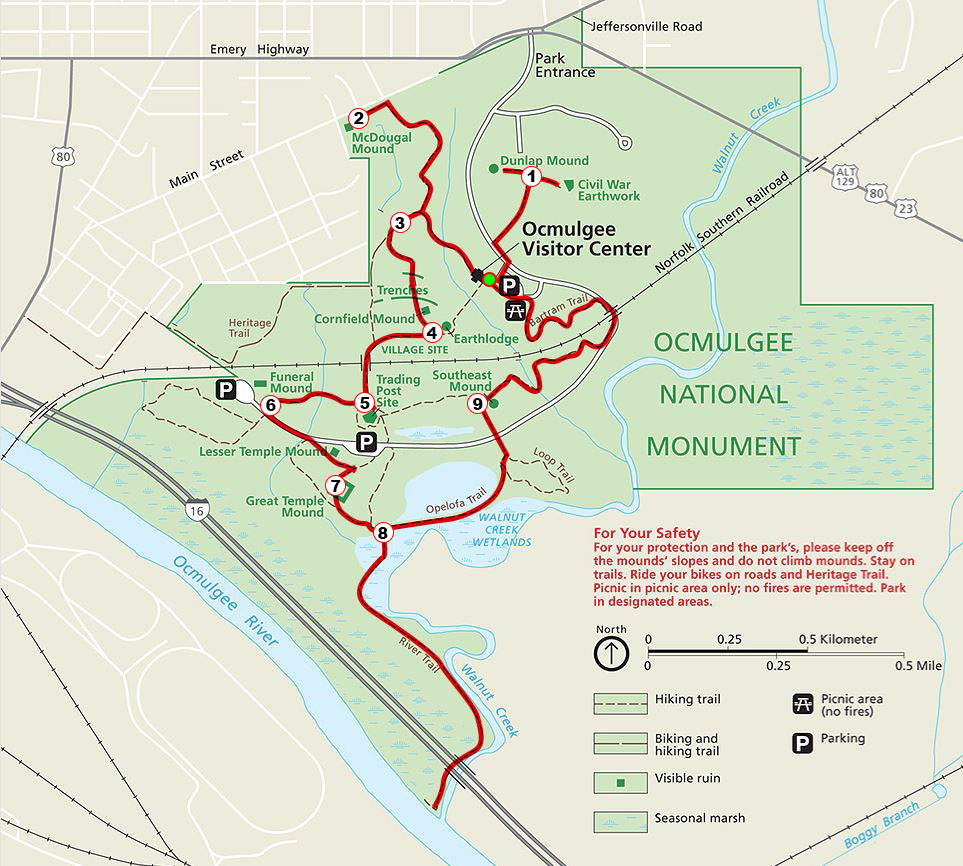

A former state legislator and Savannah mayor, Gordon spent the last decade of his life leading the construction of a railroad line between Savannah and Macon, thus connecting Georgia’s main port with the center of the state. He died in 1842, a year before its completion. In the final stages of the project the following year, his company built a railroad line over a sacred Creek tribal burial mound and the remains of a prehistoric city near downtown Macon. That land would become the Ocmulgee Mounds National Historic Park in the 1930s, and an active railroad still bisects the park today.

Both Calhoun and Gordon played a part in efforts to remove Native Americans—one out of the land and the other out of memory. But I still wondered whether the connection was just coincidence or an actual motivation for the naming. After all, you can find Calhoun’s name on counties in eleven states, cities in eight states, and numerous parks, streets, colleges, and schools across the country. The Tennessee town of Calhoun was named after him because of his role as lead negotiator in the 1820 treaty with the Cherokee (a town that ironically became a primary holding place for Cherokees prior to the Trail of Tears), but he didn’t have a prominent role in the Treaty of New Echota.

Still not satisfied, I decided to look up how nearby cities and counties in Cherokee territory were named, and I landed 1832. After Georgia ignored the Supreme Court’s Worcester decision that year, which I wrote about a few weeks ago, it distributed Cherokee land via land lottery and carved out ten new counties from the tribe’s remaining territory. I looked up the namesakes for each and found that at least half—Cobb, Forsyth, Gilmer, Lumpkin, and Cass—were named for men who played pivotal roles in efforts to expel the Cherokee tribe.

U.S. Senator Thomas W. Cobb was among a group of Southern senators and representatives who published an 1827 report arguing for their states’ rights to extend sovereignty over Indian territory to pressure them out.3 That report was a precursor the 1828 Georgia bill extending Georgia laws over Cherokee territory, signed by Governor John Forsyth. Two years later, now U.S. Senator Forsyth, along with Rep. Wilson Lumpkin, served as some of President Jackson’s strongest advocates for the Indian Removal Act of 1830. That same year, Governor George Gilmer signed into law a requirement for American citizens living within Cherokee territory to swear allegiance to Georgia law, which led to the arrest and prosecution of missionary Samuel Worcester. Then, in 1832, now-Governor Lumpkin ignored the Supreme Court’s Worcester decision and moved forward with a Cherokee land lottery. Not long after, he signed the bill that carved Cherokee territory into ten new counties, one of which was named after himself. In his memoir written years later, Lumpkin even stated that his primary motive in running for office was his “particular mission, instrumentally, to do something to relieve Georgia from the incumbrance of her Indian population, and at the same time benefit the Indians.”

Now to be clear, these men played prominent roles in the state during that era, so these actions alone aren’t enough to conclude that their roles in Cherokee expulsion motivated state legislators to name counties after them. The evolution of the fifth county’s name, however, strengthens that case.

Cass County was named for Lewis Cass, a former Michigan governor and who was serving as President Jackson’s Secretary of War at the time. Amidst intensifying debates over Southern states’ rights, why would the Georgia legislature name a new county after a presidential appointee from the North?

The April 19, 1832 edition of the Georgia Journal, an influential newspaper in Georgia’s capital of Milledgeville, provides a clue.

One month after the Supreme Court’s ruling for the Cherokee in the Worchester case, the paper printed a multi-page, spirited editorial decrying the court’s decision. The paper’s editor wrote that the article was “a most triumphant vindication of the measures and the policy of Georgia.” The author was none other than Lewis Cass, “for there is no other man in America who is at once so accomplished a scholar, so learned a jurist, and so thoroughly acquainted with the history of Indian affairs.” In his role as Secretary of War, Cass was responsible for implementing President Jackson’s Indian Removal policy, so the letter would have been interpreted at the time as the president’s public blessing for Georgia to ignore the Supreme Court’s decision. At the same time, Cass and Governor Lumpkin corresponded frequently in the aftermath of the Supreme Court’s Worcester decision to develop a plan for how to handle the imprisoned missionary. It’s in this context that legislators named Cass County after Lewis Cass.

Readers from Georgia may wonder, as I did, why we don’t have a Cass County today. The name only lasted three decades. As the nation headed toward the Civil War, Cass became a vocal slavery opponent and supporter of the Union, even resigning from his position as President Buchanan’s Secretary of State because the President wasn’t doing enough to protect federal interests in the South. Thus, in the early days of the Civil War, Georgia legislators renamed Cass County as Bartow County, this time stating the motive:

Whereas, the county of Cass . . . in its organization was named in memory of Lewis Cass of Michigan; and the said Lewis Cass having recently shown himself inimical to the South by voluntary donations of his private property to sustain a wicked war upon her people, and by utterance of sentiments such as the South must be subjugated, the Union must be preserved; and has thereby become unworthy of the honor conferred by the name of said county.

The new county name honored Francis Bartow, one of Georgia’s members in the Confederate Provisional Congress and the first Confederate general killed in the Civil War.

Given this context, the role Cobb, Forsyth, Gilmer, Lumpkin, and Cass played in Cherokee expulsion likely motivated legislators to name counties after them, at least in part. Whether that was the case eighteen years later with Calhoun and Gordon County seems less likely. But, what is clear is that a decade after New Echota’s demise, the closest Georgia town was renamed after a prominent champion of Native American expulsion and placed within a county named after a man whose company bulldozed sacred Native American burial grounds.

After visiting New Echota last February, I took the short drive down Highway 225 to downtown Calhoun. As I entered the city limits, I noticed that the welcome sign reads, “Welcome to Calhoun | Land of the Cherokee.”

The irony is that Calhoun is no longer the land of the Cherokee precisely because of men like John C. Calhoun.4

This article is the fourth in a series of seven articles about Cherokee expulsion from Georgia. The next article will step back to reflect on how places get their names and wrestle with how we should handle places with controversial names today, an issue that bubbled up again recently related to the names of buildings at Georgia’s public universities (one of which is named for Wilson Lumpkin).

If you think others would enjoy reading along too, please forward this email or share via social media.

Present-day Dawsonville in North Georgia was founded in 1857.

For an in-depth look at John C. Calhoun’s life and legacy, I found historian Robert Elder’s recent book, Calhoun: American Heretic, a thorough and readable book.

This article was originally found in Unworthy Republic by Claudio Saunt (p. 40).

Despite the irony, the sign’s acknowledgment that Calhoun is located on Cherokee land brings attention to that reality, which is better than no mention at all.