Walking Down Montgomery’s Dexter Avenue

How the competing narratives of racial oppression and racial justice play out on this short downtown street.

Perhaps nowhere in the South stacks more landmarks of racial oppression next to landmarks of resistance to that oppression than the half-mile Dexter Avenue in downtown Montgomery, Alabama.

On one end, a traffic circle encompasses the Court Square Fountain, a 25-foot, two-tiered cast iron structure topped with Greek mythological characters. The white-columned Alabama State Capitol caps the other end.

Court Square Fountain: Hub of the Domestic Slave Trade

Small streams of water spurt from each tier of the Court Square Fountain into the light blue pool below. The peaceful water feature built two decades after the Civil War conceals the decades of anguish enslaved Africans experienced in that square prior to the war.

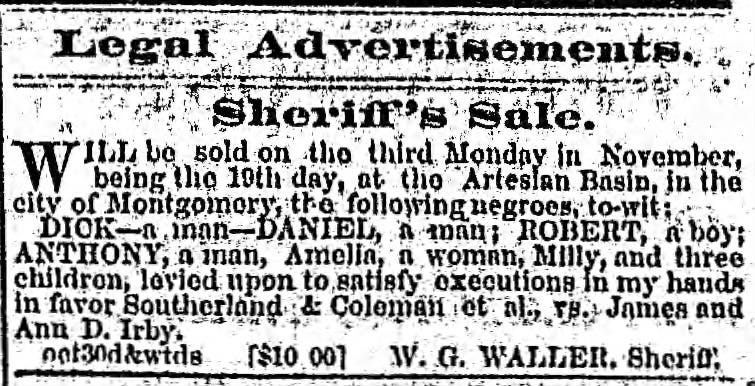

After the United States abolished the international slave trade in 1808, Montgomery’s central location, easy access to the Alabama River, and railway lines that connected much of the South made it an epicenter of the domestic slave trade. Between 1820 and 1860, Alabama’s enslaved population ballooned from 41,879 to 435,080. An estimated two-thirds were traded at some point, many of them through Montgomery’s slave market. Court Square—known then as the Artesian Basin—served as the main auction block for land, livestock, and enslaved people. Thousands of enslaved men, women, and children were brought to Montgomery by steamboat, railway, or on foot, warehoused in slave depots, sold at the Artesian Basin, and dispersed back across the South. Classified ads like the one below from the Montgomery Weekly Post appeared alongside other items for sale. The inclusion of the slaves’ names and gender alludes to their humanity, but the resulting financial transaction and family separation robbed them of their dignity.

The Winter Building: Where a Telegram Sparked the Civil War

Given Court Square’s centrality to slavery, the next landmark on Dexter Avenue is fitting. On the southeastern side of the traffic circle stands a three-story, off-white rectangular building. Above the main entrance, block lettering says “WINTER BUILDING,” and further up, “1841” hangs just below the roof. A local real estate broker’s “SOLD” sign hangs on the wall near the corner. Several broken third-floor windows indicate that the building has been unoccupied for some time.

Perhaps its present-day state is fitting for the role it played in sparking the Civil War.

From the Winter Building’s second-floor telegraph office on April 11, 1861, Confederate Secretary of War L.P. Walker sent a telegram to Confederate Brigadier General P.G.T. Beauregard authorizing him to attack Fort Sumter if American troops didn’t surrender it. The next day, Confederate forces opened fire, launching the Civil War.

Two months earlier, Confederate President Jefferson Davis’ inaugural parade passed the Winter Building down Dexter Avenue en route to the Alabama State Capitol. Four years and a day after Walker’s telegram, a different procession followed that same route through a surrendered Montgomery. Union Major General James Wilson’s cavalry rode through en route to raising the American flag at the Alabama State Capitol. A week later, they overtook Columbus, Georgia in the Civil War’s final battle and captured Jefferson Davis in rural Georgia soon after.

America’s Most Famous Bus Stop

Nearly a hundred years after Confederate leaders sent a message sparking a conflict to defend racial oppression, a Montgomery seamstress sent a message that sparked a conflict to overcome racial oppression from a bus stop across the street from the Winter Building. This battle used boycotts instead of bullets.

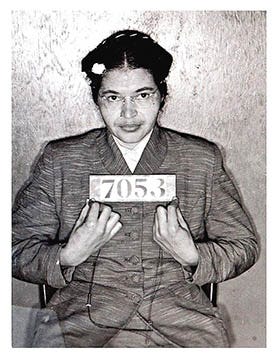

On December 1, 1955, Rosa Parks took a seat on a city bus in Court Square after work at the nearby Montgomery Fair department store. When she refused to give up her seat for a white passenger a few blocks away, her arrest kicked off the Montgomery Bus Boycott, led by the Montgomery Improvement Association and its president, a newly arrived 26-year-old pastor from Atlanta, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. His church, Dexter Avenue Baptist Church, is a few blocks away.

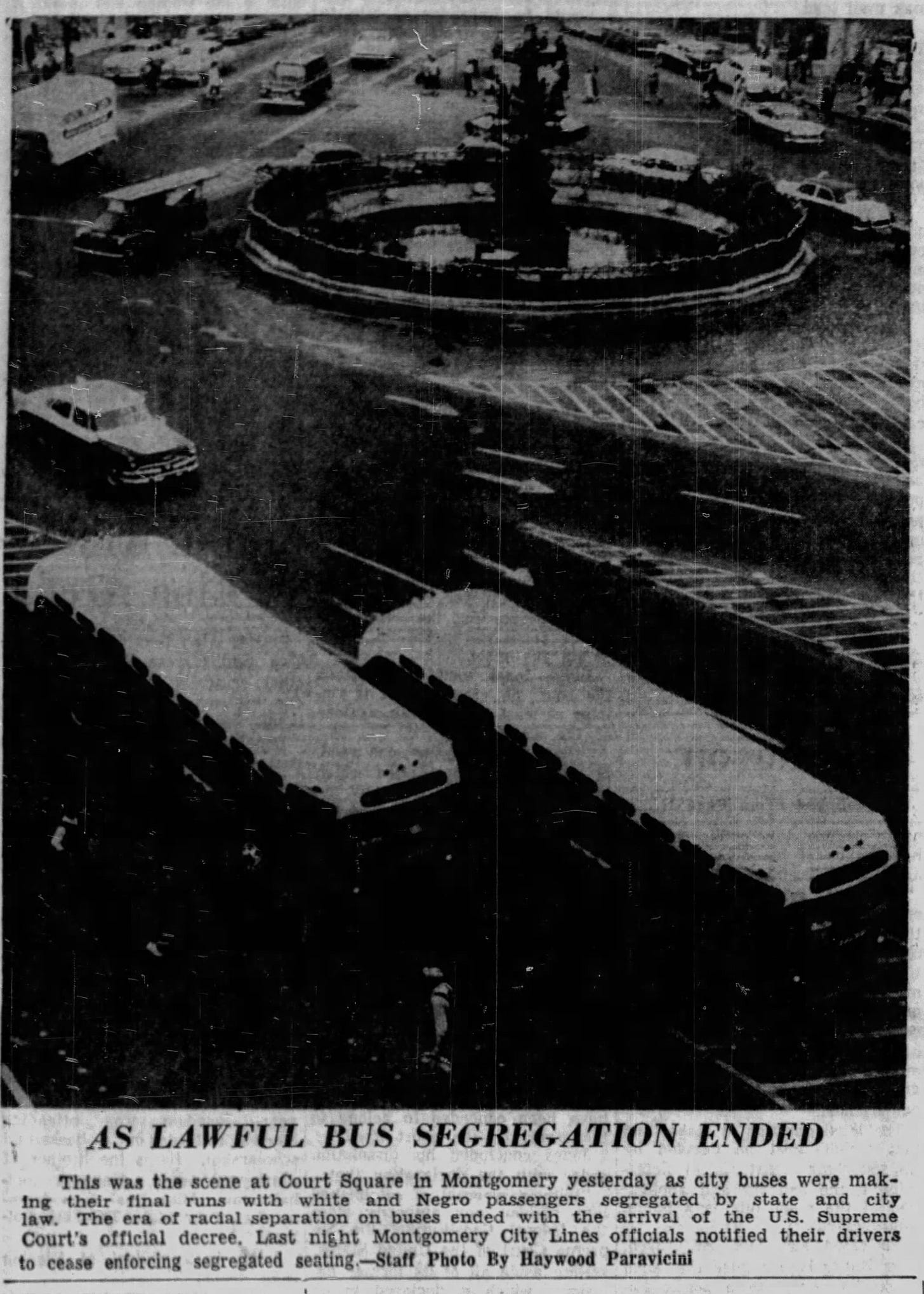

For 381 days, black Montgomery residents refused to ride segregated city buses as black leaders challenged the rule in federal courts. Many walked miles to work day after day, regardless of weather conditions. Dr. King and other leaders endured bombings of their homes and arrests for breaking anti-boycott laws, but the black community held steady until the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in December 1956 that city and state policies requiring segregation on public transportation were unconstitutional.

The non-violent tactics of the boycott brought tangible results for black Americans across the nation, and the outcome catapulted Dr. King to national leadership in the civil rights movement.

Today, a life-sized bronze statue of Rosa Parks stands on Dexter Avenue as if ready to board a bus, facing the same square where thousands of black men and women stood to be sold a few generations before her.

The State Capitol that Birthed the Confederacy . . . and Capped off the Selma Voting Rights March

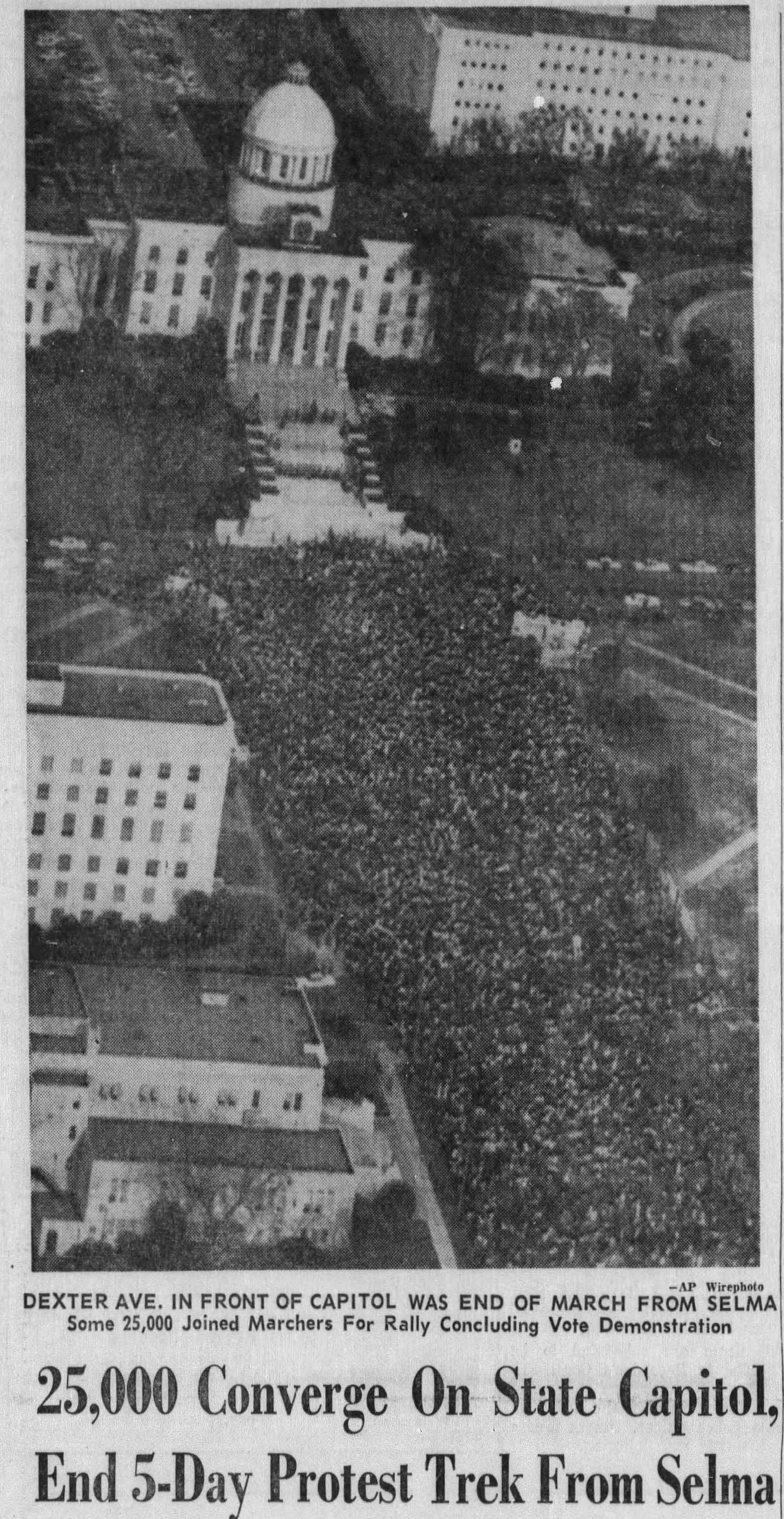

From the Court Square Fountain, Dexter Avenue climbs a slight hill in a straight line for five blocks until it dead-ends into the marble steps of the Alabama State Capitol. These stairs witnessed Confederate President Jefferson Davis’ inaugural address, but they also served as the final steps of the 54-mile, 5-day Selma to Montgomery voting rights march more than a century later.

On March 25, 1965, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. gave the culminating address to more than 25,000 people and galvanized the nation to support the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which passed months later.

Except for its wooden doors and the black clock above its columns, the Alabama State Capitol is entirely white, perhaps a metaphor for the volume of white-preserving legislation passed within its walls. Constructed in 1851, the capitol’s chambers hosted Alabama legislators when they voted to secede from the Union and, soon after, the newly formed Confederacy’s delegates as they adopted its first constitution. Much of that document mirrors the U.S. Constitution. Its Section IX includes much of the Bill of Rights but adds the constitutional right to slavery, stating that “no bill of attainder, ex post facto law, or law denying or impairing the right of property in negro slaves shall be passed.” The new nation left no ambiguity that could allow further generations to abolish slavery.

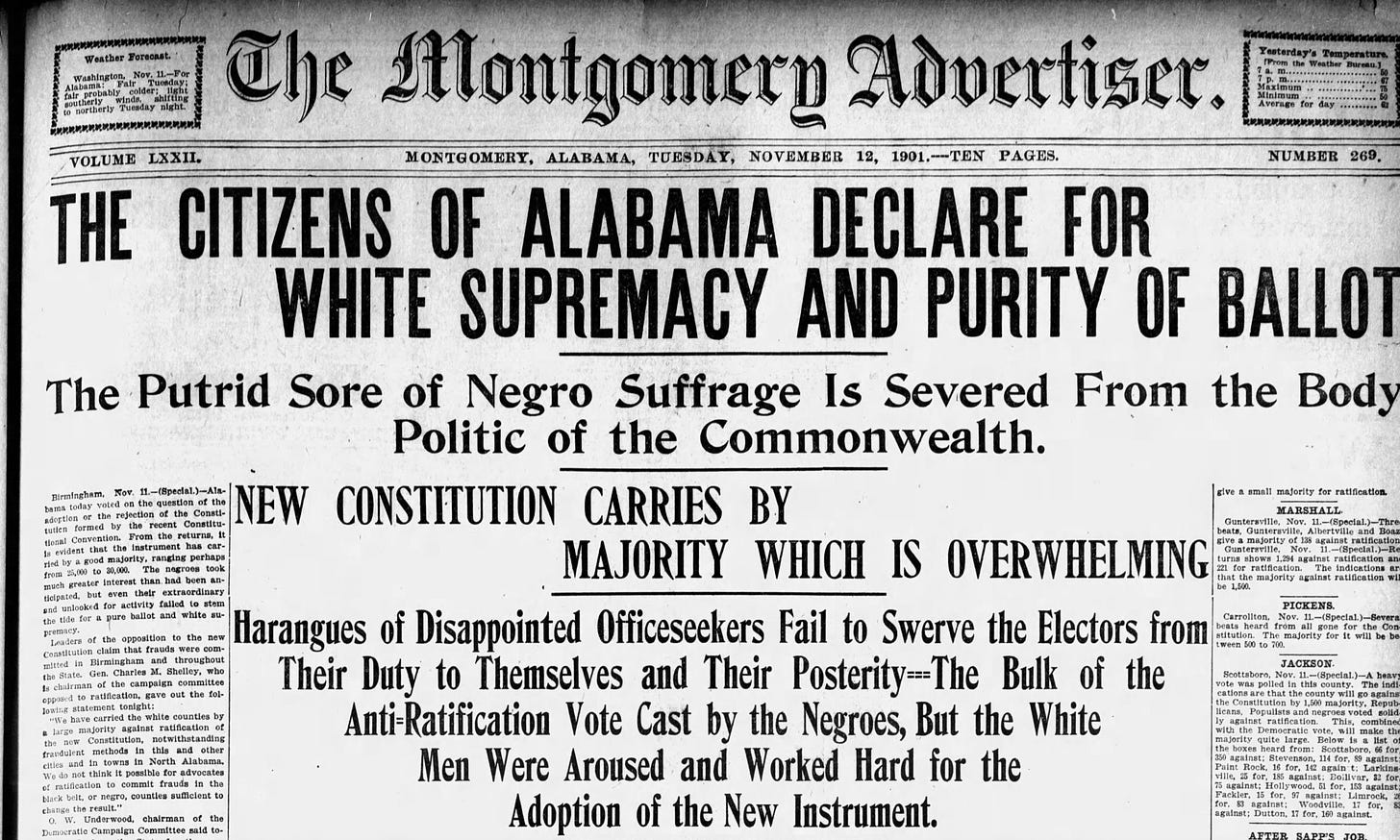

After the Confederacy’s defeat in 1865, federally-enforced Reconstruction offered a decade-long window of black voting and legislative representation in the state capitol. Voter intimidation and the withdrawal of federal protection soon undercut progress, returning ex-Confederates and white supremacist legislators to power. The 1901 state constitution culminated these efforts. The Montgomery Advertiser’s headline the day after the state referendum didn’t even try to hide the motives, “The Citizens of Alabama Declare for White Supremacy and Purity of Ballot: The Putrid Sore of Negro Suffrage is Severed from the Body Politic of the Commonwealth.” After the constitution’s implementation, only 3,000 of the more than 180,000 black males of voting age remained registered to vote.1

Six decades later, there was no better place for Dr. King to call the country to account for its disenfranchisement of black Americans than those capitol steps on Dexter Avenue.

Dr. King’s Church

The imposing state capitol building towers over the end of Dexter Avenue, especially in comparison to the two-story, red-bricked Dexter Avenue Baptist Church, where Dr. King pastored from 1954-1959. On the day after Rosa Parks’ arrest, King called a meeting in the church’s basement that launched the bus boycott.

The peaceful scene when I visited on a Thursday afternoon in February belies what it must have been like on a given day during King’s tenure at the church. Each building served as an anchor for planning and galvanizing support for how to oppose the actions of those in the other, separated only by a few steps. If Dr. King were to take a walk around the block before a Sunday sermon or make the 15-minute trek home to the parsonage, how often would he have walked past white Alabama leaders determined to quash his rights as a black man?

Making Sense of Dexter Avenue

The bookends of Dexter Avenue—a slave auction block and the state capitol—symbolized two bastions of white supremacy. One, the seat of commerce. The other, the seat of government. Both leveraged white supremacy to oppress generations of black Alabamans. But in between those symbols, black leaders like Dr. King and Rosa Parks galvanized local black residents to undercut those efforts not with brute force and violent action but with non-violence and love. As Dr. King closed his 1965 voting rights march address on the capitol steps, a full decade after the bus boycott thrust him into the national spotlight, he reminded those gathered of what lay ahead:

I must admit to you that there are still jail cells waiting for us, and dark and difficult moments. But if we will go on with the faith that nonviolence and its power can transform dark yesterdays into bright tomorrows, we will be able to change all of these conditions. And so I plead with you this afternoon as we go ahead: remain committed to nonviolence. Our aim must never be to defeat or humiliate the white man, but to win his friendship and understanding. We must come to see that the end we seek is a society at peace with itself, a society that can live with its conscience. And that will be a day not of the white man, not of the black man. That will be the day of man as man.

We’ve made progress toward that vision, but we haven’t realized it yet. As we yearn toward that future, Dexter Avenue provides us with overlapping opportunities to lament our painful past while at the same time finding the perseverance to fight the next struggle for racial justice.

Today’s article draws from my participation in the OneRace Movement’s Southern Justice Experience at the beginning of February 2024, a two-day visit to civil rights landmarks in Birmingham, Selma, and Montgomery alongside metro Atlanta pastors and leaders. The OneRace team led a walking tour from the Alabama River to Dexter Avenue Baptist and unpacked many of these stories.

A Personal Note

When I last posted on Southbound, my wife, Hannah, and I had been home only a few weeks after an extended NICU stay in Florida with our adopted son, Luke. Since then, Luke has had successful heart surgery and continues to make medical progress. Adjusting to our new life as a family of five—along with a busy season at work—left little margin for writing. The ideas are still there; just not the time to research and write. I plan to write when I can in the months ahead, but Southbound articles will still be hit-and-miss. Thank you for continuing to read.

Franklin, John Hope. From Slavery to Freedom, Vintage Books (1969), p. 341