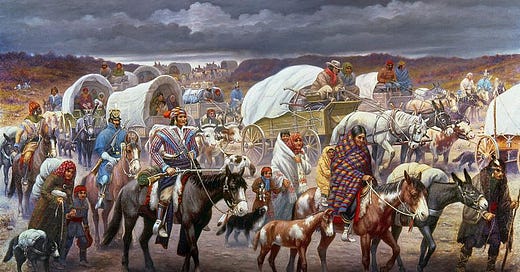

The governing authorities of the conquered land forced them to make a multi-day trek amidst treacherous conditions. Underlying health conditions didn’t matter—even late-term pregnancies couldn’t delay the journey.

The authorities, along the soldiers tasked with enforcing their orders, viewed the people who lived in that land as uncivilized and incapable of accomplishing great things. In fact, they viewed all people of that ethnic group as inferior.

During the Christmas season, we hear statements like these describing Mary and Joseph’s 90-mile trip from Nazareth to Bethlehem in compliance with a Roman census in 1st century Palestine, even as she was about to give birth to Jesus. But, if we step back for a minute, those words were also true of the Cherokees in 19th century Georgia as soldiers forced them from their land on what became known as the Trail of Tears.

This juxtaposition struck me last Sunday morning as I reflected on the Christmas story, causing me to detour from my planned Southbound article for this week. Originally, I scheduled this week’s article to focus on how places get their names. But, as we head into Christmas tomorrow, that article can wait a couple weeks. I recognize that not all Southbound readers celebrate Christmas. If that’s you, my hope is that the reflections below will shed light on how my faith undergirds my learning and writing journey.

Jesus was born to a poor, unwed mother in a barn. He grew up in the backwoods town of Nazareth, which placed his family at the fringes of the Jewish people, who were at the fringes of the Roman empire. Years later, Nathaniel, a soon-to-be apostle of Jesus, heard where he grew up and expressed in shock, “Can anything good come out of Nazareth?”

Similarly, the prevailing 19th century American view of the Cherokees and other indigenous nations was that they were irredeemable and primitive, as summarized by President Andrew Jackson in 1833:

That those tribes cannot exist surrounded by our settlements and in continual contact with our citizens is certain. They have neither the intelligence, the industry, the moral habits, nor the desire of improvement which are essential to any favorable change in their condition.

This context made me wonder where and to whom Jesus would have been born had he arrived in 1830s America instead of 1st century Palestine. Given the similarities above, a likely candidate would have been a full-blooded Cherokee mother as she was forced out of her home in the North Georgia Mountains. This is certainly more probable than the white American mother poised to move onto that land, despite her supposed faith in the same God.

And, as Jesus grew up and brought healing and restoration to Cherokee and non-Cherokee alike, I imagine many Cherokees would have grown frustrated by his unwillingness to overthrow American oppression. After all, why have supernatural power and not use to liberate your people? At the same time, Jesus’ ability to gather crowds would have made many white Americans feel threatened. What if the Indians all unify and rebel to take back their land? And, of course, his skin color would be too dark for them to consider the truth of his message.

Sometimes a story doesn’t sink in until we put it in a context closer to home.

For me, this thought experiment renewed a spotlight on white American Christians’ theological blind spot, enabling them to rob fellow humans of their dignity and inflict misery on them.1 But then that spotlight shifted to the list of theologians, pastors, and writers who have shaped my faith journey. Many are white. Few lived in contexts where they were oppressed like 1st century Jews or 19th century Cherokees. None are indigenous. In fact, until the last few months, I’d never sought to understand the complex faith journey of Native American followers of Jesus.

There’s a richness of faith beyond my comprehension for a Native American to follow Jesus despite all the wars, broken promises, land theft, and abusive boarding schools that supposed Christians inflicted on their people for the last five centuries. Faith forged in contexts like Jesus’ deserve a certain respect that those forged in contexts like the Romans can’t earn. And yet, my pride had led me to prefer theologians whose faith developed in relative safety, power, and comfort (like mine!). They may know the original Greek and Hebrew, which is important, but they can’t put themselves in the shoes of the oppressed. While not saying it outright, my choices revealed an underlying assumption that indigenous perspectives on Jesus weren’t worth my time.

In Revelation 7, the Apostle John describes a vision of heaven where an enormous crowd from “from all tribes and peoples and languages” is worshipping God together. We’re going to be shoulder to shoulder on that day. In the meantime, I’ve got a lot of listening, learning, and reading to do to make up for lost time. Perhaps you do too.

This is a one-off article amid my six-article series about Cherokee expulsion from Georgia. In two weeks, I’ll return to the schedule with an article reflecting on how places get their names and wrestling with how we should handle places with controversial names today.

If you think others would enjoy reading along too, please forward this email or share via social media.

Historian Jemar Tisby’s book, the Color of Compromise, provides a thorough account of the American church’s complicity in racism, particularly toward black Americans.