Making Sense of Cherokee Expulsion from My Homeland

The Cherokee Trail of Tears started twenty miles from where I grew up. I never gave it much thought, at least until November 2020.

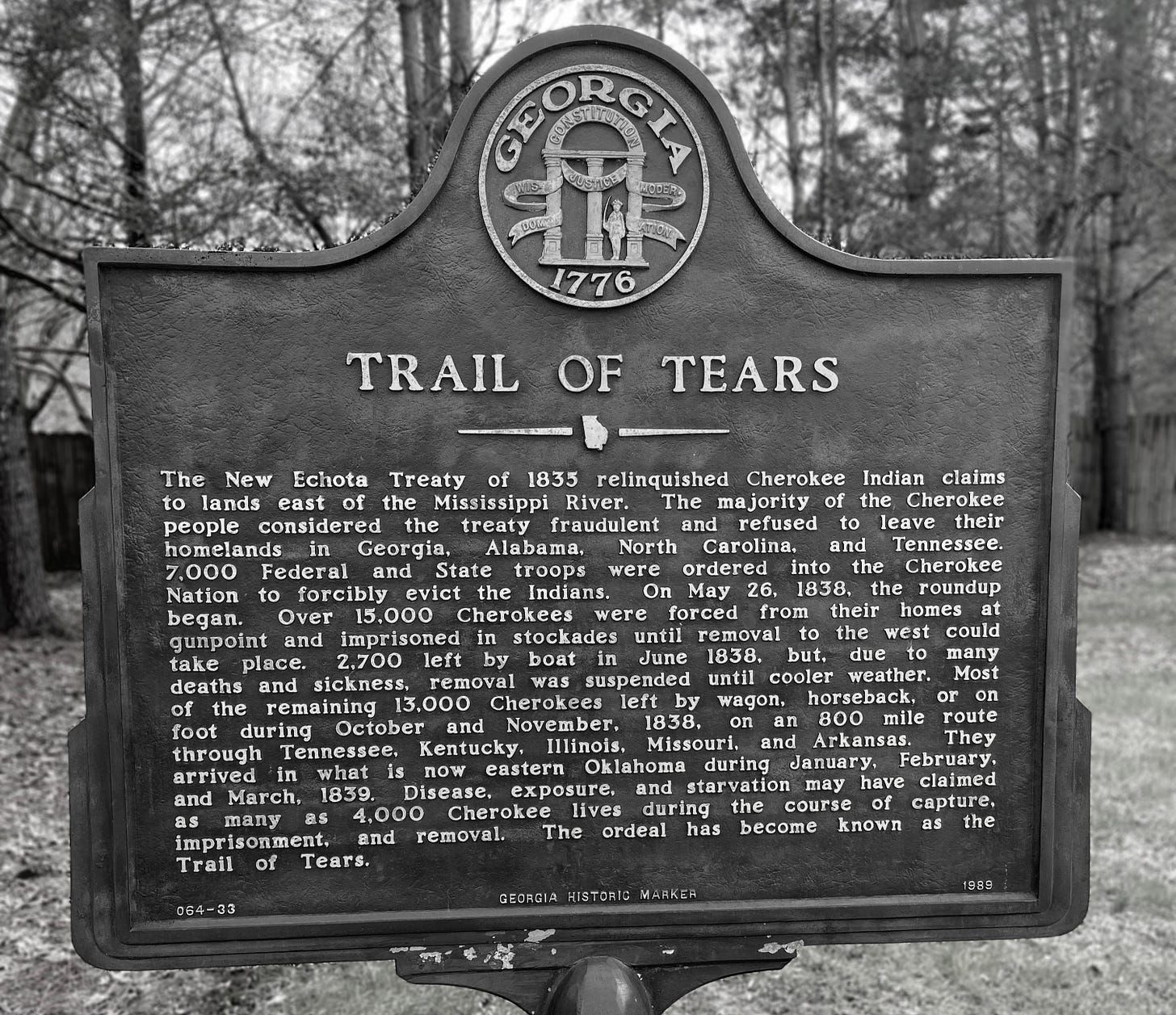

In the late 1830’s, American troops drove 16,000 Cherokees from their homeland, which is now my homeland, to the Oklahoma territory 1,200 miles away. A fourth of them died on the way. And yet, this history was little more than a gloomy footnote to my childhood understanding of Georgia history. I visited Cherokee sites like New Echota and Red Clay on school field trips. I traced letters in the Cherokee alphabet. I knew that the Trail of Tears happened, but it felt like a distant tragedy, an event perpetrated by evil men generations ago that had little relevance to me today.

Over the last decade, I’ve been on a journey to learn a more complete picture of our nation’s history and wrestle with its implications today. Much of that process has focused on black history, but at the back of my mind Cherokee history loomed as a topic I knew I needed to explore someday but that felt distant enough that I could ignore it, at least for now. It was akin to a home deck repair that keeps getting pushed down the priority list by other pressing repairs. The problem is, if ignored long enough, the deck will collapse.

The deck started to crack last November when I queued up the next episode of the podcast, American History Tellers, on my drive home from the office one day. The podcast’s season at the time covered the stories of landmark U.S. Supreme Court cases, and that particular episode was called “The Cherokee Cases.” I was intrigued but unprepared for the next 45 minutes, which would destabilize my benign neglect of Cherokee history.

Since that day, I’ve read what I can find on Cherokee expulsion from Northwest Georgia. I’ve visited several sites, including New Echota, the Cherokee Capital near Calhoun, and the Chief Vann House near Chatsworth. The Cherokee story is far more complex than I expected, with surprising turns that don’t fit easily into categories. I’m still wrestling with the legacy of Cherokee expulsion from land that my ancestors would inhabit a mere thirty years later.1 It has forever changed how I view our country and how that period of time fits in with the broader history of the South.

Now it’s time to bring others into that process too. In the coming months, I’ll publish a series of Southbound posts on various aspects of the Cherokee expulsion story and how I’m processing its meaning today. This Thursday, the first piece will share the overarching story of the Cherokee tribe’s deportation from Northwest Georgia and Southeast Tennessee, commonly known as the Trail of Tears. In the weeks that follow, I’ll explore aspects of the story in more detail, such as the time Georgia’s governor persecuted American missionaries or how the names of Northwest Georgia cities and counties today relate to Cherokee expulsion.

As you read, I encourage you to post comments or questions so that we can all continue learning.

-

Update with Links to Published Stories Below

Part I: The Inevitable Expulsion - October 28, 2021

Part II: When Georgia Persecuted Christian Missionaries - November 11, 2021

Part III: An Unlikely Time for a Memorial to Racial Injustice - November 26, 2021

Part IV: Welcome to Calhoun | Land of the Cherokee? - December 10, 2021

Part V: Why Do Most Georgia Rivers Still Have Native American Names? - April 1, 2022

Part VI: When Place Names Don’t Reflect Our Values - May 13, 2022

Part VII: Closing the Cherokee Chapter - December 6, 2022

I prefer using the term “expulsion” or “deportation” rather than the more commonly used “removal.” As historian Claudio Saunt argues in his book, Unworthy Republic, these words more rightly fit what happened to the Cherokee and other tribes rather than the more passive sounding “removal.”

It was sad for me passing thru Oklahoma, home to 17 (I believe) different tribes of Native Americans, whose main livelihood now seems to be owning and running casinos. I too look forward to your research.

I’m looking forward to reading these posts. I appreciate your interest in and sense of responsibility for reporting these historical events (and for writing articulately & concisely about history I should have researched long ago).