The Inevitable Expulsion

The Cherokee tribe adapted to stave off deportation. In the end, it was a battle they were never going to win. Part I of a six-article series on Cherokee deportation from Georgia.

I first visited the New Echota State Historic Site in Northwest Georgia on an elementary school field trip, a twenty-minute ride down I-75 from the town of Dalton where I grew up. Like most school-aged kids taking a field trip, my friends and I were more excited at the chance to get outside the school building for a day than caring about where we were going.

When we pulled up, reconstructed log cabins and town buildings dotted a tree-lined field along the side of the two-lane Highway 225. Inside each structure, dining room tables were set and beds were made to show what life was like in the Cherokee capital before the tribe’s expulsion from Georgia. They looked much like early American cabins I’d seen in pictures of the frontier—certainly nothing like the wigwams or teepees often associated with Native Americans in our textbooks.

What stood out from that day was the park guide demonstrating the tribe’s 19th century printing press. In the early 1800s, a Cherokee named Sequoyah created an alphabet, the first Native American tribe to do so. A few years later, he and others raised funds to purchase a printing press and produce the Cherokee Phoenix, the first Native American newspaper.

We watched the park guide crank the wheel and press down the ink-covered pad onto the light brown paper, before pulling the paper out and hanging it to dry on the rafters. I remember feeling dejected because he skipped me when giving away several copies to students. I don’t remember feeling dejected because of the tragedy that occurred where I was standing. I don’t remember considering what my life would have been like if the Cherokee Nation had remained. Where would I be living? Would my parents have met? What would Northwest Georgia look like today?

I had a lot of catching up to do this year when I decided to dig into the Cherokee tribe’s history in Georgia.

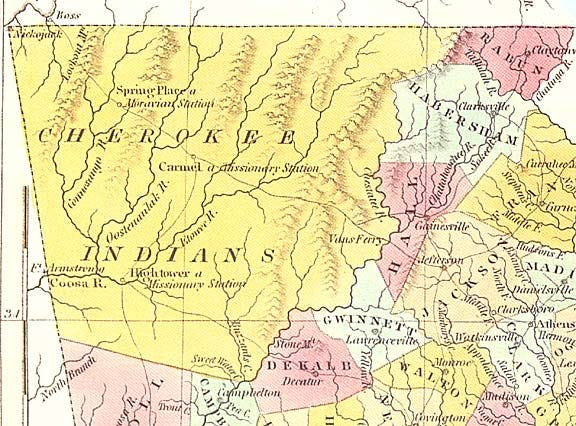

Designated the Cherokee Nation’s capital in 1825, New Echota sits where the Coosawattee and Conasauga Rivers combine to become the Oostanaula River, about four miles northeast of present-day Calhoun, a town that serves as the county seat of Gordon County. New Echota’s founding was the culmination of Cherokee efforts to incorporate certain aspects of white Americanism into their practices while still maintaining distinctiveness from their neighbors.

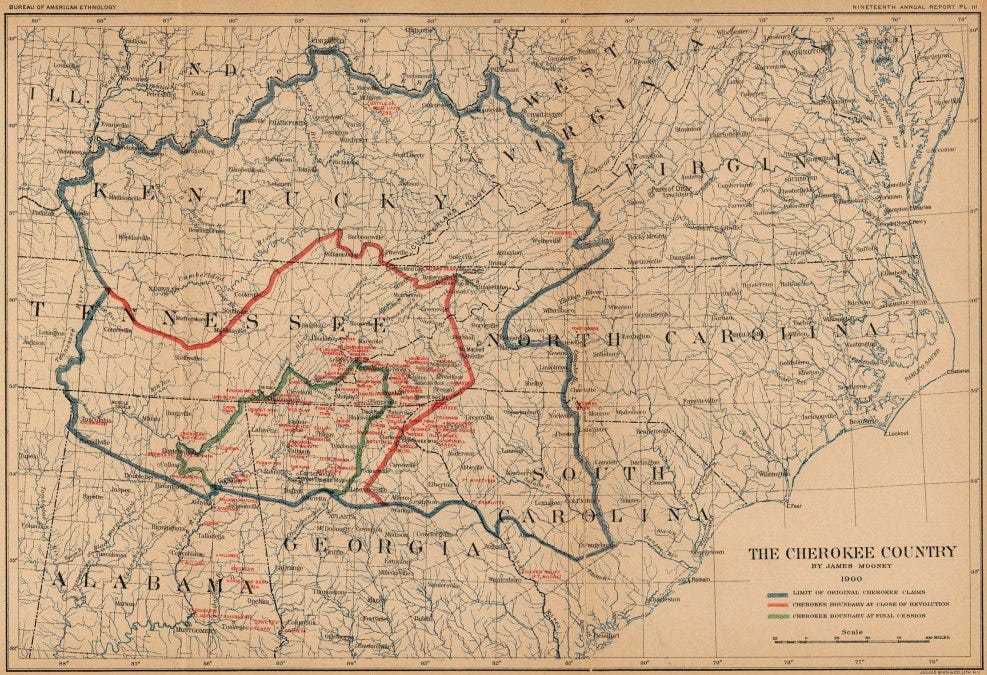

The Cherokee tribe had lived in the present-day U.S. South for generations, holding as much as 80 million acres in the early 18th century.1 As white European explorers and then settlers entered the land, they traded with the Cherokee but skirmishes and battles also ensued. Throughout the 1700’s, the Cherokees entered into a series of treaties with the British that chipped away at its land in hopes of staving off settler encroachment. When the Revolutionary War broke out, the tribe allied with the British, which made for a rocky early relationship with the newly born United States after the war.

Hope for peaceful coexistence came in 1791, just two years after the U.S. Constitution went into effect. With George Washington as president, the U.S. government and the Cherokee Nation entered into the Treaty of Holston to end nearly a decade of conflict and bloodshed between white American settlers and the Cherokees. The treaty stated:

There shall be perpetual peace and friendship between all the citizens of the United States of America, and all the individuals composing the whole Cherokee Nation of Indians.

It also established territorial boundaries, recognized the Cherokee Nation’s sovereignty under the protection of the United States, guaranteed no American citizen could settle or hunt on Cherokee land, and set up annual federal government payments to the Cherokee Nation.

Although the treaty seemed straightforward, it did not slow settlers and surrounding state governments from pressuring Cherokees to cede land. Just eleven years later, that same federal government, this time under Thomas Jefferson, violated the treaty without Cherokee input. The State of Georgia ceded present-day Alabama and Mississippi to the federal government in exchange for a promise to “extinguish the Indian title to all the other lands within the State of Georgia” as soon as they could be “peaceably obtained, on reasonable terms.” Even though the U.S. Constitution places treaties as more authoritative than an agreement like this one, it still laid the groundwork for future expulsion.

As years passed, white settlers’ insatiable hunger for land led them to continue setting up homesteads on Cherokee land. Government officials did nothing to stop them. Instead, the federal government ramped up efforts to “civilize” tribes like the Cherokee with education, Christianity, and technology. In contrast to surrounding tribes, some Cherokee leaders embraced this investment, even sending their children off to New England boarding schools so they could bring the best of white culture back to the Cherokee. They believed that their best chance of retaining their land and sovereignty was to demonstrate their advancement by assimilating certain aspects of white American culture.

At the advice of President Thomas Jefferson in an 1808 White House meeting, Cherokee leadership drew up a constitution and modified their council government to resemble the American government’s three branches. They invited taxpayer-funded missionaries to come live in their nation and set up schools to educate Cherokee children. The wealthiest even set up plantations and purchased African slaves to work on them, emulating the planter culture throughout the South at the time.

Despite these efforts, state governments surrounding the Cherokee Nation plodded forward with attempts to secure the land, as they had already done with other Native American nations. Still, progress and protection seemed possible. That optimism took a blow in 1828 when a white settler found gold on the border of Cherokee land in present-day Lumpkin County, causing a flood of new settlers to the area in hopes of riches.

Later that year, the Georgia legislature enacted a law that extended its sovereignty over Cherokee land—an outright affront to the Treaty of Holston—and stripped due process and property rights from Cherokees. Then, in 1830, it passed a law that outlawed Cherokee government proceedings and required any white men living within Cherokee territory to register with the governor and swear allegiance to Georgia laws, including Christian missionaries who had lived with Cherokee for years. The federal government, under President Andrew Jackson, was no better. One of his top 1828 campaign promises had been Native American expulsion to the West (despite having an adopted son, Lyncoya, who was from the Creek tribe). In 1830, Congress passed the Indian Removal Act at his urging, authorizing the removal of Native Americans to western territories.

Soon after Georgia’s new law went into effect, the Georgia Guard, a quasi-militia force the state legislature empowered to oversee Cherokee territory, arrested eleven missionaries when they refused to comply with Georgia’s new law. Nine agreed to leave the state, but two, Samuel Worcester and Elizur Butler, pled not guilty and appealed to Georgia’s governor for release. They were nonetheless convicted and sentenced to four years of hard labor in Milledgeville’s state prison.

After strategic assimilation for the several decades in hopes of holding off expulsion, the Cherokees played their strongest hand yet. Samuel Worcester and the Cherokee Nation sued Georgia, given the Georgia law’s direct contradiction with the Treaty of Holston. The case jumped straight to the U.S. Supreme Court since it dealt with sovereignty between the two. Surely, they thought, the highest court would uphold the U.S. Constitution and honor its treaty.

And, they were right. In March 1832, the Court ruled on behalf of Cherokee sovereignty and overturned the Georgia law, with Chief Justice John Marshall writing the 5-1 majority opinion.

The Cherokee Nation, then, is a distinct community occupying its own territory . . . in which the laws of Georgia can have no force, and which the citizens of Georgia have no right to enter but with the assent of the Cherokees themselves, or in conformity with treaties and with the acts of Congress. The whole intercourse between the United States and this Nation, is, by our Constitution and laws, vested in the Government of the United States.

At last, victory.

Or so they thought.

President Jackson and Georgia’s governor, Wilson Lumpkin, refused to enforce it. Jackson supposedly remarked, "John Marshall has made his decision, now let him enforce it.”2 Georgia’s legislature moved forward with the inclusion of unceded Cherokee land in its next land lottery for white settlers. Soon after, the Georgia Guard began evicting Cherokee families from their land. During this time, it was common for a white settler to show up at a Cherokee home, knock on the door, and demand the family to leave his property. As proof, he would show a deed from the State of Georgia entitling him to the land and even the house that the Cherokee family had built. If the Cherokees refused to leave, he would have the Georgia Guard forcibly remove them.

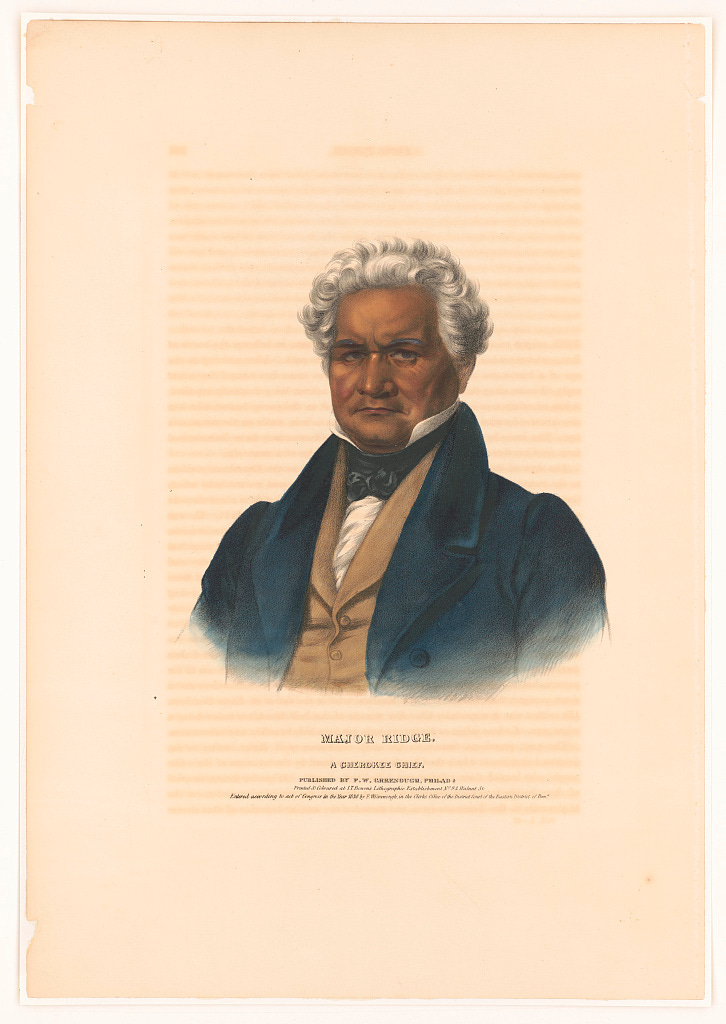

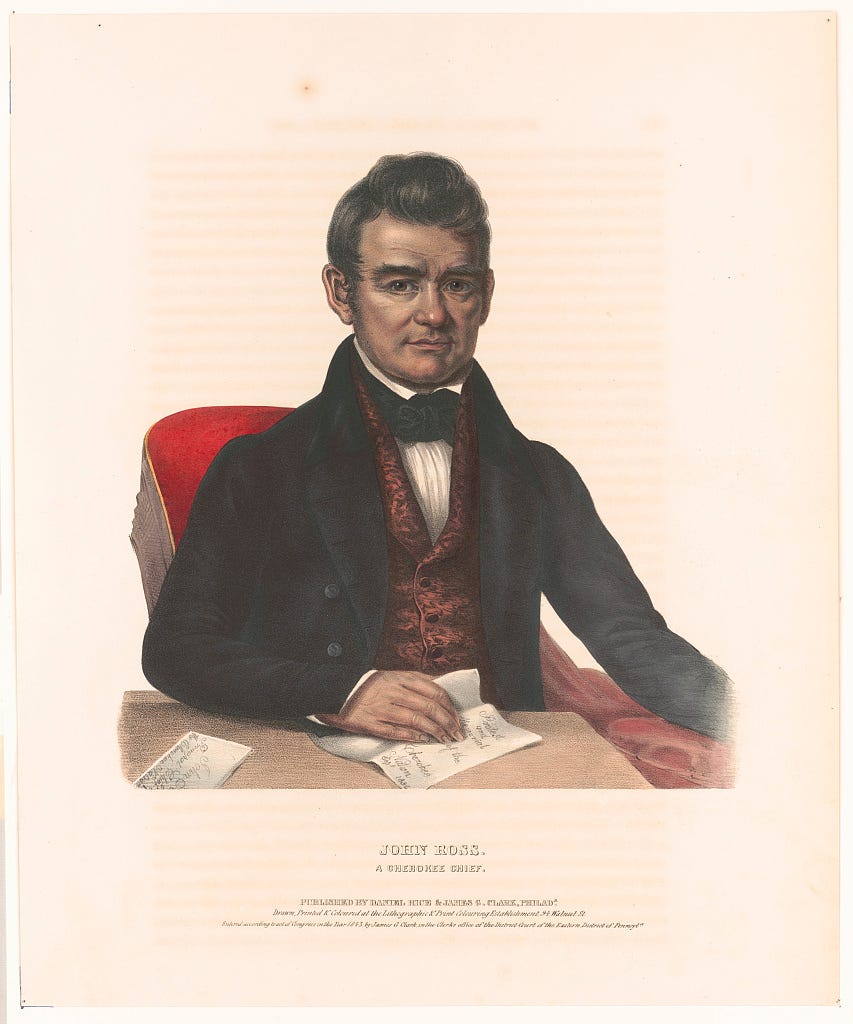

With the Supreme Court ruling ignored and no relief in sight from Georgia’s violent harassment, a small but powerful subset of Cherokees led by Major Ridge, his son John Ridge, and Elias Boudinot, gave up hope of eventual peace and retention of land. Their faction, which became known as the Treaty Party, believed that losing their land was now inevitable; thus an agreement with the Jackson administration could save lives and salvage some reimbursement . The elected chief, John Ross, continued to hold out hope, and a significant majority of the Cherokee people followed his lead.

Seeing what they believed was best for their nation, the Treaty Party negotiated and signed the Treaty of New Echota on December 29, 1835, sending it to the U.S. Senate for approval. By signing the treaty, party leaders knew they were breaking a Cherokee law they had supported years before that called for the death penalty for any Cherokee who ceded land to surrounding governments. In exchange for the remaining seven million acres of Cherokee land, the federal government agreed to pay $5 million, provide comparably-sized land in present-day Oklahoma, and give the exiles provisions for the trip west.

Chief Ross refused to sign the treaty, and once it became public, he petitioned the U.S. Senate with thousands of Cherokee signatures opposing ratification. Two months later, after intense debate, the Senate voted to ratify the treaty by a margin of just one vote.

Given the significant opposition to the treaty, President Van Buren (Jackson’s hand-picked successor) provided a two-year window for Cherokees to voluntarily leave. Only two thousand did so. As a result, in May 1838 federal troops under General Winfield Scott began forcing the remaining 16,000 Cherokees and their slaves off their land, first to hastily built stockades, one of which stood 250 yards south of New Echota. Soldiers pulled men out of fields. Families were sometimes separated as they were given mere minutes to leave. Greedy white settlers swooped in to gather whatever possessions were left behind, sometimes even while the distraught Cherokee families watched on their march away.

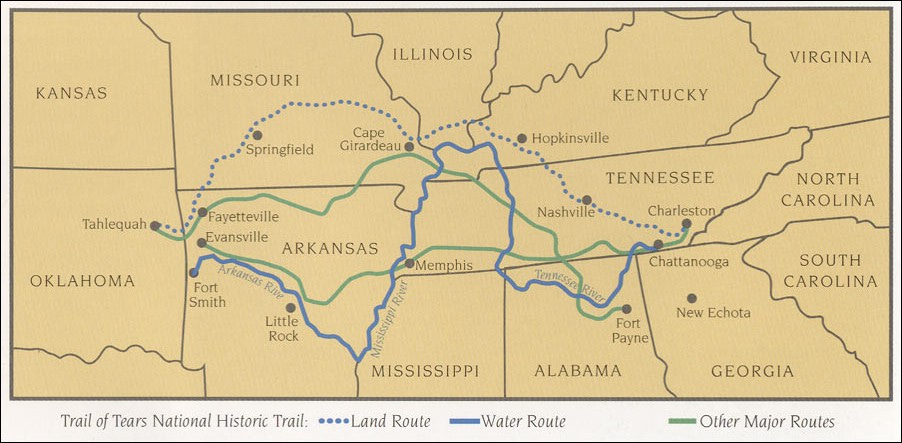

Some left in caravans to Oklahoma not long after being apprehended, while others spent months in squalid conditions at the stockades to wait out the summer heat. The final group completed the 1,200-mile trek to Oklahoma in March 1839. In total an estimated 4,000 Cherokees, a fourth of the population, died from sickness, disease, and exhaustion during the expulsion.

Tragedy didn’t end there. Not long after their arrival in Oklahoma, bands of Cherokee men murdered Treaty Party leaders Elias Boudinot, Major Ridge, and John Ridge on June 22, 1839 in retribution, kicking off a Cherokee civil war that would last for decades, even resulting in the two sides allying with opposing sides during the U.S. Civil War.

As I unwound the events and people that led to Cherokee expulsion from Georgia, a deep sense of lament overcame me. I needed to sit with what was done. I needed wrestle with why the story’s details were a footnote—and the Cherokee people a footstool—for our collective memory of Georgia history. Why had I learned so much about the Holocaust on the other side of the Atlantic Ocean but so little about Cherokee expulsion in my backyard? Maybe you’re in that place right now. Don’t rush it. Often, we skip or scurry past this critical step—I know I do.

I was also struck by the story’s many layers. I hadn’t known that a white missionary had been a plaintiff in the Cherokees’ Supreme Court case. I hadn’t known that Cherokees held slaves too. I wondered whether today’s city and county names—like Lumpkin County or the town of Calhoun—may be related to Cherokee deportation. I wondered about the story behind New Echota becoming a state-funded historic site when that same state government had forced the town’s founders from their land generations earlier. Maybe you’re curious about these questions too.

Over the next few months, I’ll dig into these questions and others that forced me to reckon with the past and how we remember it. In two weeks, the second article will take a deeper dive into the story behind Georgia’s persecution of American missionaries in the lead-up to Cherokee expulsion.

If you think others would be interested in reading along, please consider forwarding this post or sharing via social media. And, please comment with your thoughts or questions below.

This article is the first in a seven-part series on Cherokee deportation from Georgia. In addition to the direct links within the article, the books below were used as reference:

Trail of Tears: The Rise and Fall of the Cherokee Nation - John Ehle (easiest to read for a narrative of events)

Unworthy Republic: The Dispossession of Native Americans and the Road to Indian Territory - Claudio Saunt

Jacksonland: President Andrew Jackson, Cherokee Chief John Ross, and the Great American Land Grab - Steve Inskeep

The Cherokee Nation and the Trail of Tears - Theda Perdue and Michael D. Green

Driven West: Andrew Jackson and the Trail of Tears to the Civil War - A.J. Langguth

This post primarily focuses on the Cherokee tribe’s interactions with the United States and Georgia. Much more could be written about Cherokee life prior to the United States’ existence as well as European arrival on the continent.

Historians debate whether Andrew Jackson actually said these words, but they don’t debate that this was his posture toward the decision.

Man, thanks for writing this. I just got around to reading it. Good stuff.

During my years of teaching, I took a dozen classes to New Echota and heard the history you explained in this blog. In spite of having to listen with one ear to the video and the other to disturbances from my class (who, like you at that age were eager to get through this “boring” part and into the great outdoors), I do remember being affected by the story and having a sense of the injustices done here. The difference now is that I can look & listen with a different heart that is open to different perspectives and not willing to claim “manifest destiny” as a justification for what was done to the Cherokee people, or worse, just not really care. These times and young people like you, Sam, can help us all become people who have a genuine desire for a world where all people matter and no single group can have exclusive control.