An Unlikely Time for a Memorial to Racial Injustice

What the New Echota State Historic Site's opening ceremony decades ago can teach us about our blind spots today. Part III of a seven-article series on Cherokee deportation from Georgia.

On a warm May afternoon, Georgia’s governor gave a somber address dedicating a site that memorialized a century-old injustice to a people of color. Not far from where he stood, the military had forced families to leave their homes at gunpoint, often without warning, sometimes even separating families. In his address, the governor apologized “for the unbridled avarice of our ancestors,” while descendants of the wronged listened on stage. In the days leading up to the event, the state legislature unanimously repealed laws that had sanctioned the systemic injustice. The event, and the site itself, called on Georgians to remember the past and ensure that it didn’t happen again.

You would be forgiven for thinking this ceremony happened recently—or perhaps for even questioning whether it ever happened.

But I doubt you would guess that it happened in 1962.

The governor was Ernest Vandiver, the same governor elected four years earlier on promises to buck court-ordered desegregation with “no, not one” black child entering a white classroom. The defrauded people were the Cherokee Nation, who in 1838 were forced to leave their ancestral land on the Trail of Tears to make room for land-hungry white Georgians, as I described in the first article in this series last month. The site was New Echota, the Cherokee capital just outside the present-day town of Calhoun in Northwest Georgia. The repealed laws were those that had stripped the Cherokees of their land, their ability to testify in court, and their authority to govern.

So, against the backdrop of increasing racial tensions over civil rights, Governor Vandiver held a ceremony bringing attention to and apologizing for racial injustices committed by white Georgian ancestors. Why would the leader of a state bent on maintaining the racial status quo hold a ribbon cutting for a site lamenting an injustice done to another people of color within the same state?

As I considered this question, I came across historian Andrew Denson’s book, Monuments to Absence: Cherokee Removal and the Contest over Southern Memory, which helped me put together the pieces.

To tell the story, we need to rewind back to New Echota’s demise in 1838. The white Georgians who won it in the state’s land lottery tore down the buildings and converted it into farmland. Only the home that had belonged to Samuel Worcester, the missionary we discussed two weeks ago, and a small cemetery survived. As the decades passed and the nearby town of Calhoun expanded, locals knew New Echota’s general location. The name Echota persisted in local memory too, showing up in the name of a significant Calhoun cotton mill in 1907 and several local churches founded in the first few decades of the 1900’s.

In 1925, the Calhoun Women’s Club set out to memorialize key moments in the town’s near 100-year past. It constructed a statue of Sequoyah, the inventor of the Cherokee syllabary, just northeast of downtown Calhoun at the intersections of Highway 41 and 225. At the same time, the women built the Calhoun War Memorial steps away, a stone arch commemorating local Confederate and World War I veterans. A soldier from each war is perched on either side of the arch, as if standing guard at the city’s edge.

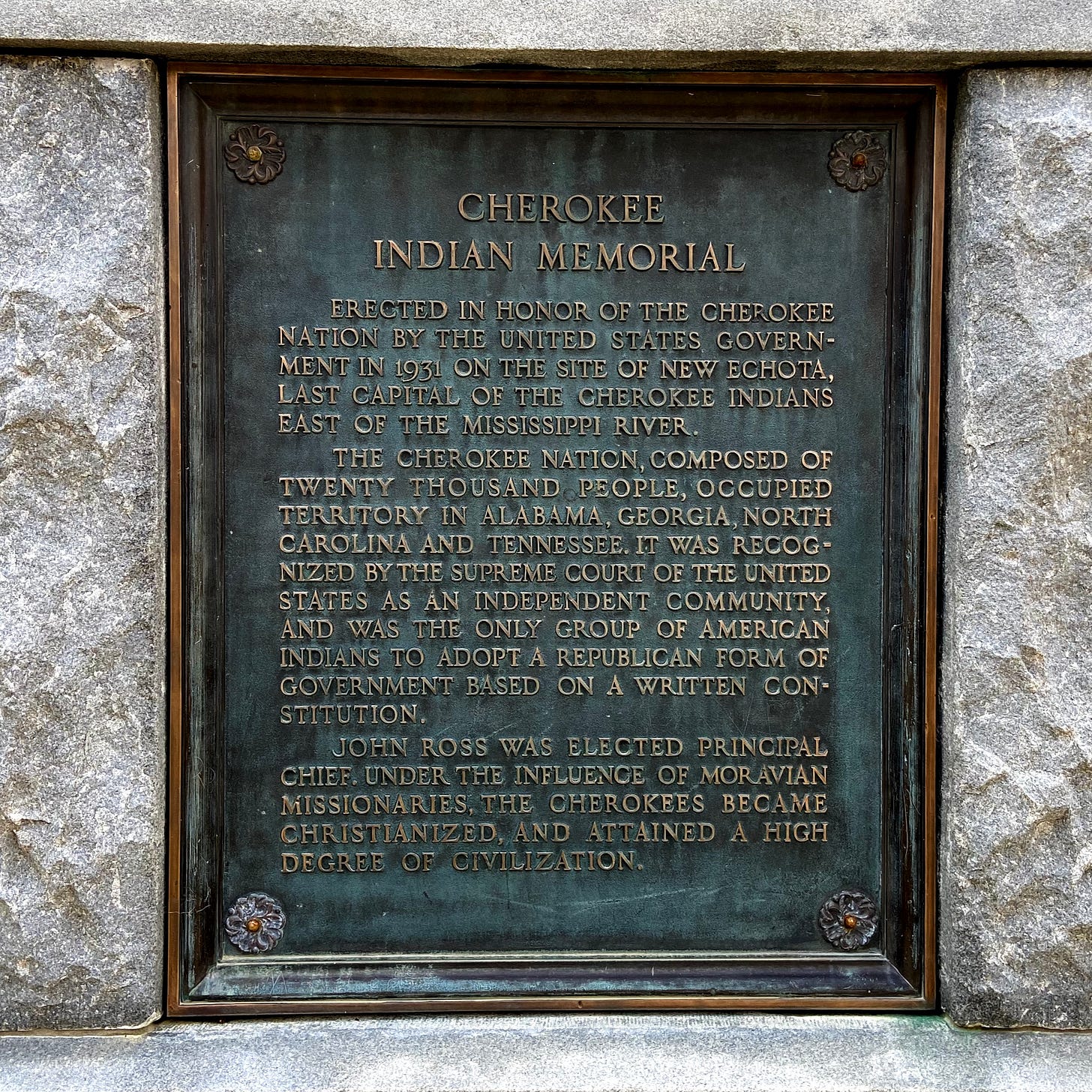

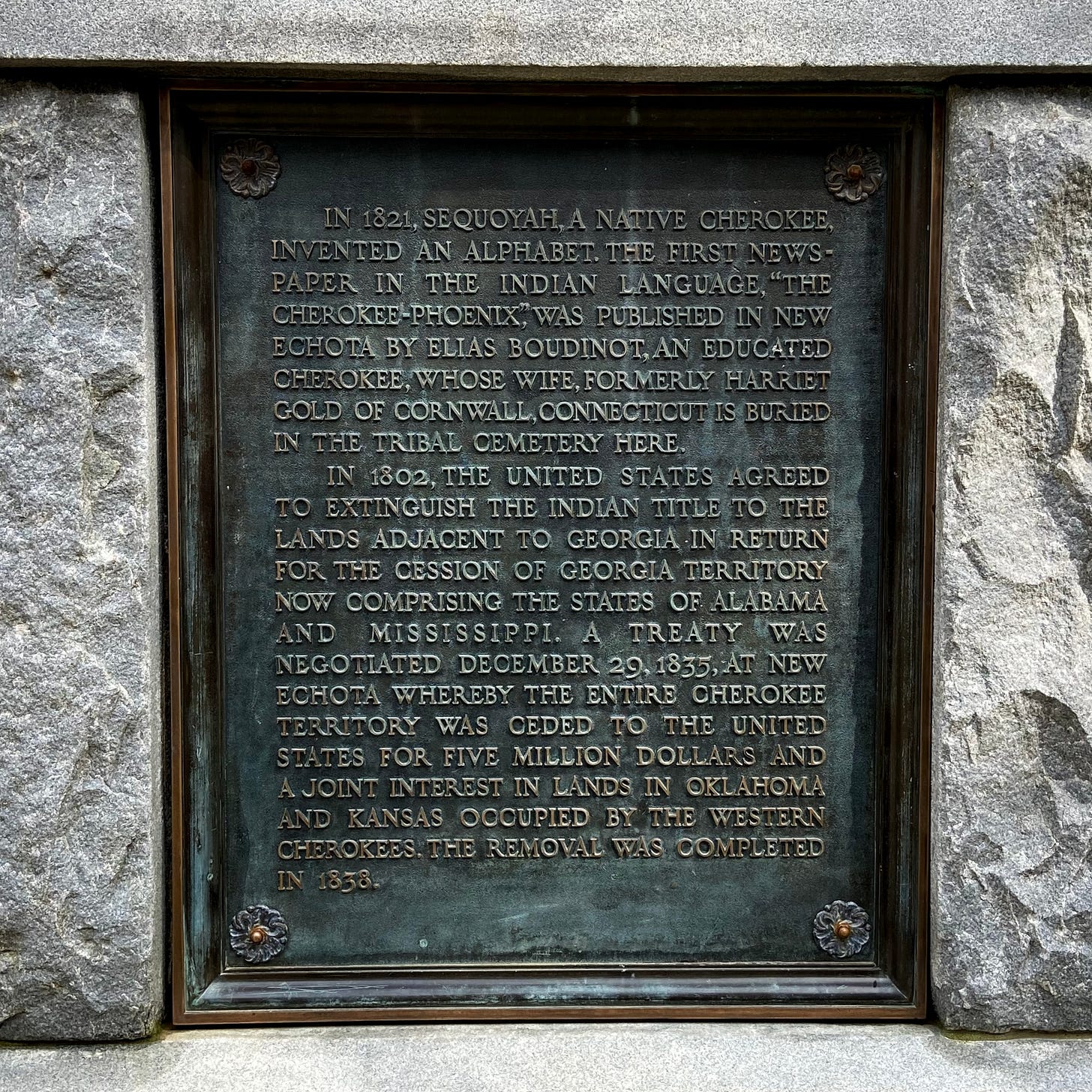

Five years later, Congress authorized $2,500 to install stone boulder and plaque on an acre of donated land where New Echota once stood. The plaque, “erected in honor of the Cherokee Nation,” uses matter-of-fact language to praise the civilization and Christianization of the Cherokee before describing the treaty of New Echota that ceded the land to the federal government.

When I read over the plaque’s description of events, its use of passive voice stuck out to me. A treaty “was negotiated . . . whereby the entire Cherokee territory was ceded. . . . The removal was completed in 1838.” The wording allows for ambiguity on who did what to whom—namely who negotiated the treaty (a small subset of Cherokees) and who removed the Cherokee (the U.S. Army). Its dispassionate tone doesn’t force the reader to wrestle with any implications. And, it’s a far cry from Governor Vandiver’s speech thirty years later. So, what changed in the intervening years?

The next step in New Echota’s restoration came in the 1940s. To promote tourism, the local chamber of commerce raised funds to hire a historian to pinpoint New Echota’s location and petitioned the newly formed Georgia Historical Commission to support the work. Their work received a boost in 1950 when Congress transferred ownership of New Echota, along with several nearby Civil War battle sites, to Georgia’s public park system. Around the same time, locals purchased the 220-acre original site and transferred the deed to the state to create a historic site.

Local leaders’ focus on tourism was common during the post-World War II era in the South as more families had automobiles and new highway systems simplified travel. Denson describes the draw of New Echota’s attractiveness:1

New Echota was a unique place, the seat of a Native American government. It also occupied a favorable location, close to Calhoun’s downtown and only a short distance from Highway 41, an important autoroute connecting the cities of Atlanta and Chattanooga.

Local leaders often referenced the success of Cherokee sites in Western North Carolina as well as Colonial Williamsburg as models for success, hoping New Echota would become a “little Williamsburg.” At the state level, in 1957 the legislature authorized the reconstruction of buildings on the land. After listing Cherokee accomplishments and local efforts to identify the location, the bill states:

The reconstruction of "New Echota" will provide the great State of Georgia with one of the most important tourist attractions in the United States of America; and . . . through the reconstruction, establishment and development of this valuable tourist attraction, it is completely estimated that upon completion it will greatly add to the State's revenue through sales and gasoline taxes alone.

In short, the efforts focused more on recreating what life was like in the Cherokee capital as a way to attract visitors and generate tax revenue than on lamenting the injustice of its demise.

By the time of the park’s 1962 opening, the historical commission had restored the Worcester house as well as reconstructed both the Cherokee Supreme Court building and the Cherokee Phoenix’s printing office.

But if tourism was a primary motive for local and state leaders in the historic site’s creation, why did state leaders repeal anti-Cherokee laws ahead of the opening ceremony and use their speeches to apologize for their ancestor’s greed? Around the same time, Georgians had complained that the historical commission’s work at Civil War sites had painted their Southern ancestors in too negative a light. And yet, New Echota’s commemoration escaped similar critique despite its potential to do the same.2 What made it different?

The answer seems to be one of proximity and time. For many white Georgians, the 1830s were far enough in the past and the Cherokee people lived far enough at a distance that confronting ancestral sins brought limited costs.

Cherokees who visited New Echota would return to their homes outside of Georgia’s borders. Georgia’s leaders could show remorse with limited tangible costs in the present, while enabling them to claim a measure of moral uprightness. The legacy of slavery and the Civil War, on the other hand, allowed no such escape. Descendants of the enslaved were plentiful throughout Georgia, and Jim Crow-era segregation was still the law of the land. Denson writes:3

While acknowledging the evils of black slavery or segregation could point toward a remaking of southern society, acknowledging removal required only monuments.

There’s another wrinkle here too though. If you pay close attention to the narrative Governor Vandiver shared on that stage in 1962, you hear the Cherokees portrayed as a civilized and honorable people who just wanted to have their way of life preserved. Instead, they were overrun by cruel outsiders who had no right to intervene. For those familiar with the South, that framing sounds similar to the whitewashed portrayal of Southerners’ motivations for fighting the Civil War—defending honor, protecting a certain way of life, and fighting for sovereignty—which was especially common during the civil rights era. Thus, at a time when many white Georgians were protesting the Supreme Court’s enforcement of civil rights, they found solace in lamenting the “civilized” Cherokees’ plight at the hands of their ancestors who also refused to follow the Supreme Court’s orders.

When I drove to New Echota back in February, I took a brief detour through the Resaca Battlefield, the site of a May 1864 battle as part of Union General Sherman’s March to the Sea that accelerated the Civil War’s end. Later that day, as I stared at New Echota’s historical marker just four miles away, I was struck by how little time passed between New Echota’s demise and the Battle of Resaca. Just 26 years. That’s the same amount of time between the Atlanta Braves’ World Series title in 1995 and the one last month. I have vivid memories of watching both. In the same way, many Georgians at that time would have had vivid memories of receiving Cherokee land in Georgia’s land lotteries as they fought to defend the Confederacy years later.

White Georgians fought to defend their land from “Northern Aggression,” but we forget that they had only held that land for a short time after their own campaign of Southern Aggression against the Cherokees.

Over the last year, we as a nation have wrestled with how we remember the past in public spaces. We’ve built new memorials to tell a more complete version of the past, while we’ve debated and sometimes removed Confederate memorials (like the General Johnston’s statue in my hometown just north of New Echota).

When I think about the story behind New Echota’s remembrance, I’m struck by how easy it is for me to be like Governor Vandiver on that stage, decrying the injustices of the past while tolerating or ignoring the injustices of the present.4 Hindsight allows me to pick apart his and others’ motives, see their moral inconsistencies, and congratulate myself for being so righteous. But, I wonder what my grandchildren will think when they look back at my life. Where will they stare in disbelief, wondering how I could tolerate such an injustice? Where will they see ulterior motives and question my commitment to justice? Put simply, where will they see blind spots that I’m content to ignore?

For us to continue our country’s lurching march toward justice, we must lament the injustices of the past. Sites like New Echota are an important part of that process. But, as we take steps in that direction, we also must be on the lookout for our own version of Vandiver’s New Echota that can inflate our egos and blind us from seeing where we fall short today.

This article of part three of a seven-part series on the Cherokee tribe’s expulsion from Georgia. In the next edition, we’ll circle back to key figures in Georgia’s efforts to expel the Cherokee, including Governors Lumpkin and Gilmer, and reflect on how Georgia cities and counties received their names.

If you’ve benefited from reading this series, please consider forwarding it to your friends or sharing via social media. Please leave a comment with your reflections or questions.

Denson, A. (2017). Monuments to Absence: Cherokee Removal and the Contest over Southern Memory. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press. p. 115

Ibid, p. 128

Ibid, p. 108.

In fairness to Vandiver, he softened some of his rhetoric and policies toward desegregation as his term in office wound down. In 1961, he recognized that desegregation was unavoidable due to court orders and pushed the legislature to repeal laws prohibiting state funds for institutions that desegregated, opening the doors for the University of Georgia and Atlanta Public Schools to desegregate. Given this shift, his response stands in contrast to his counterparts in Alabama and Mississippi who continued their opposition.