When Georgia Persecuted Christian Missionaries

A closer look at Samuel Worcester and his role in the story of Cherokee expulsion. Part II of a six-article series on Cherokee deportation from Georgia.

“If I suffer in consequence of continuing to preach the gospel and diffuse the written word of God among this people, I trust that I shall be sustained by a conscience void of offence, and by the anticipation of a righteous tribunal from which there is no appeal.”

For those who grew up in or attend church, the statement above may sound familiar. It mirrors words we’ve heard many times from Christians who are persecuted for their faith, starting with the Apostle Paul in the New Testament and carrying forward to today in other parts of the world. It’s a statement of ultimate faith—a willingness to suffer or die for the sake of spreading the Gospel.

But what jarred me about this specific statement is that it didn’t come from another country, or even another state. It was written right here in Georgia, not far from where I grew up. Samuel Worcester, a U.S. citizen serving as a missionary to the Cherokee tribe, wrote it in an 1831 letter from his home in present-day Northwest Georgia to Georgia’s governor, George Gilmer.1 He argued that a recently enacted state law requiring him to take an oath of allegiance to Georgia laws, which stripped Cherokees of the right to own property and testify in court, would undermine his credibility with them. Refusing to do so, however, meant Worcester would face a four-year sentence of hard labor in a Milledgeville state prison.

Two weeks ago, I shared the overarching story of the Cherokee tribe’s expulsion from Georgia as part one of a seven-article series. This post unpacks Samuel Worcester’s story in more detail, one which I’d never heard until listening to an American History Tellers podcast last November. Not only did Worcester play a central role in the fight over Cherokee sovereignty, but Georgia leaders’ treatment of him spotlighted their unbridled greed and hypocritical Christian faith.

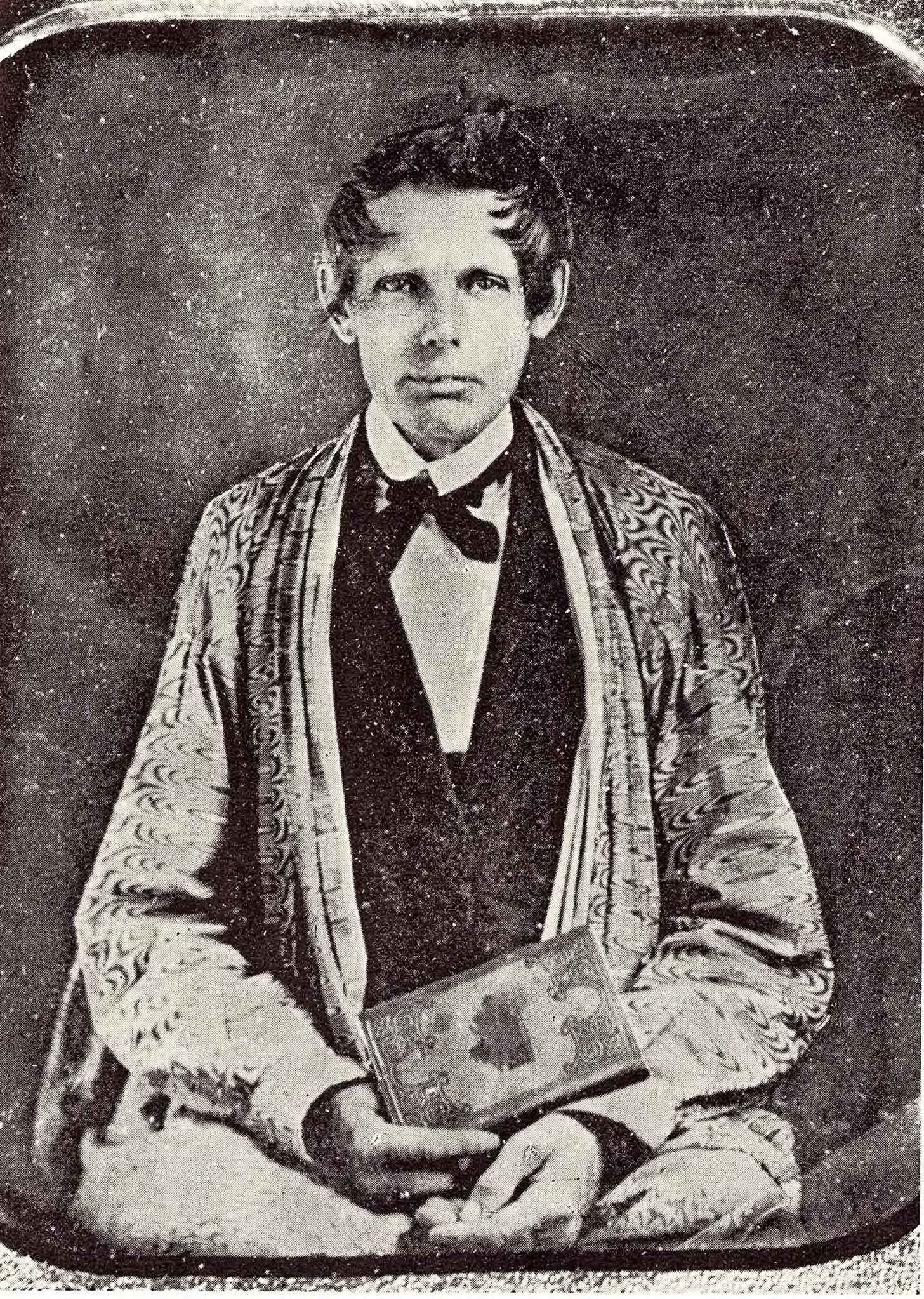

But first, we need to rewind and explore how Worcester came to live among the Cherokee tribe. Six years earlier in 1825, the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions (ABCFM) assigned Samuel Worcester, a 27-year-old recent seminary graduate from Vermont, and his wife, Ann, to the Brainerd mission in Cherokee territory near present-day Chattanooga. The language in his commissioning demonstrated a blend of evangelism and colonialism. His goal was “to make the whole tribe English in their language, civilized in their habits and Christian in their religion.” The ABCFM had a deep-pocketed partner in this effort—the U.S. government’s Bureau of Indian Affairs created by Secretary of War John C. Calhoun—which partially funded ABCFM’s missions to educate and modernize tribes into white American culture (the intermingling goals of evangelism and “civilization” of tribes is its own essay for another time).

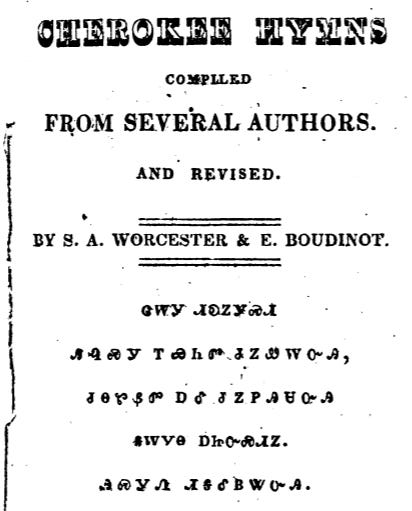

Upon moving, though, Worcester soon left behind the first goal of imposing English as the tribe’s language. Instead, he set out to learn the Cherokee language, and with the recent development of a Cherokee syllabary, he began translating the Bible and hymns into the language. Worcester became close friends with Elias Boudinot, a half-Cherokee/half-white tribal leader who had converted to Christianity while away at a boarding school in Connecticut. In 1827, the Worcesters moved forty miles south to live near the Boudinots in New Echota, which had recently become the Cherokee Nation’s capital. They built a house a short walk from the town’s center and the Boudinots’ home.

The pair set out to raise funds for printing press that would enable the creation of the first Native American newspaper, the Cherokee Phoenix. Printed in both English and Cherokee, the paper’s goal was twofold: to keep the Cherokee people united and informed amid increasing encroachment from Georgia settlers and to spread the Cherokee perspective to more hospitable readers across the United States. In addition to its editorial views, they hoped the Cherokee Phoenix would provide tangible evidence to white Americans that the tribe could modernize, making deportation west unnecessary. For Worcester’s local ministry, the printing press also enabled more efficient printing and distribution of his translated Bibles and hymnbooks.

Months after the Cherokee Phoenix’s first issue in February 1828, which included an editorial arguing against settlers’ continued encroachment on Cherokee land, Georgia’s legislature passed laws stripping due process and land ownership rights from Cherokees. It also extended state jurisdiction over their territory—calling the Cherokee “tenants” on Georgia land. To put this in context, a white Georgian could assault a Cherokee man in Cherokee territory, and as long as another white man didn’t witness it, the victim couldn’t contest the aggressor’s account in court.

Even though these laws were a direct affront to the U.S. government’s treaties with the Cherokee, President Andrew Jackson’s administration looked the other way. With what seemed like free rein to pressure the Cherokee, Georgia’s legislature set its sights on another perceived barrier to expulsion—white Americans who lived among the Cherokee and supposedly encouraged their stubborn hold on the land. It passed a law requiring all white men living in Cherokee territory, other than federal agents, to swear allegiance to Georgia laws by March 1, 1831 or face four years of hard labor in a state penitentiary. The law also banned all Cherokee government meetings and court proceedings, and it created a new militia, known as “the Georgia Guard,” to enforce the law.

This latest incursion put men like Worcester in a bind. Taking the required oath would mean consenting to Georgia’s ownership of Cherokee land, the denial of Cherokee due process rights, and the invalidation of any Cherokee government authority. That was a non-starter. However, refusing to take the oath meant certain arrest and imprisonment hundreds of miles away from the tribe and their families.

When the law went into effect, Governor Gilmer sent the Georgia Guard to notify Worcester and other missionaries of the law and their impending arrest if they refused to comply. Most refused. So, on March 13, 1831, Worcester and others were arrested without a warrant and taken on foot and horseback eighty miles to Lawrenceville for a court hearing. Worcester argued that he and others should be exempted as federal agents, both because the federal government partially funded their missionary work and, in his case, due to his role as New Echota’s postmaster. The judge released them on this technicality, and Worcester returned home to his family.

Frustrated with the outcome, Governor Gilmer asked President Jackson for help. He swiftly fired Worcester as postmaster and assured the governor that the federal government did not view missionaries as its agents. Three weeks later, Gilmer wrote Worcester notifying him that his exemptions were no longer valid and that if he chose to remain, he would be arrested again.

In response, Worcester decided to appeal to Governor Gilmer directly—as a fellow Christian who might relent if he saw the benefit of his missionary work. He recounted the progress in preaching and translation of hymnals and portions of Scripture. Along with his letter, he sent a translated copy of the book of Matthew and a hymnbook. In addition to the quote at the beginning of this post, he argued that taking an oath to Georgia law would undermine his ministry, saying:2

Such a course, even if it were innocent to itself would, in the present state of feeling among the Indians, greatly impair, or entirely destroy my usefulness as a minister of the gospel among them. It were better, in my judgment, entirely to abandon my work, than so to arm the prejudices of the whole people against me.

Gilmer was unmoved. He sent the Georgia Guard anyway, and they arrested Worcester as he concluded a church service, forcing him to leave behind his wife and two kids. To make matters worse, his wife was still recovering from a recent childbirth that ended with the tragic loss of their baby.

The soldiers arrested ten others across Cherokee territory before heading back to Lawrenceville. This time around, the soldiers had less respect for their prisoners. One sergeant regularly mocked them by saying, “Fear not, little flock, for it is your Father’s good pleasure to give you the kingdom.” Several were chained by the neck to horses and forced to walk on foot the entire journey.

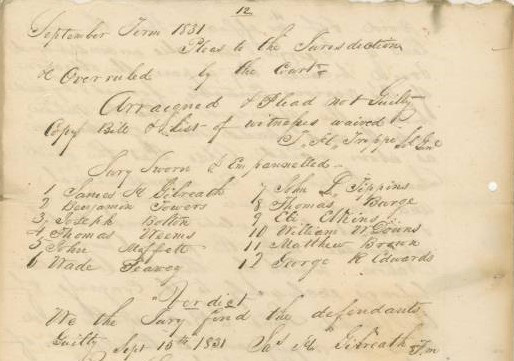

Before trial, nine missionaries cut a deal to leave the state in lieu of conviction. Only Worcester and another missionary, Dr. Elizur Butler, refused to budge. Both were convicted and sent to the state penitentiary in Milledgeville in September 1831.

For me, learning this part of the story hit close to home—literally. Worcester was arrested down the road from where I grew up, convicted in the county where I live now (Gwinnett), and imprisoned on the same square block where I attended college. The barracks where he slept in prison were located on the exact location where I took my political science undergraduate courses.

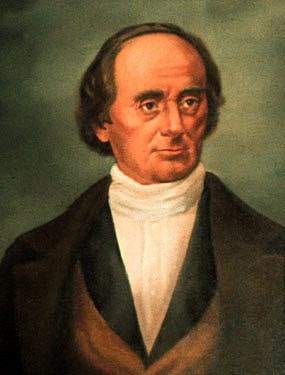

The conviction set up an ideal legal case for Worcester and the Cherokee Nation to sue Georgia and invalidate the new laws as counter to prior treaties between the federal government and the Cherokee Nation. In fact, six months after Worcester and Butler’s conviction, the Supreme Court ruled 5-1 in the Cherokees’ favor and overturned Georgia’s laws. However, Georgia’s recently elected governor, Wilson Lumpkin, who had been a key champion for Jackson’s Indian Removal Act as a U.S. Congressman a few years earlier, refused to release Worcester nor acknowledge that Georgia’s anti-Cherokee laws were null and void. He focused his ire on the Supreme Court’s overreach on states’ rights, arguing in his 1832 Annual Message to the states’ citizens:

Our conflicts with Federal usurpation are not yet at an end. The events of the past year have afforded us new cause for distrust and dissatisfaction. Contrary to the enlightened opinions and just expectations of this and every other State in the Union, a majority of the judges of the Supreme Court of the United States have not only assumed jurisdiction in the cases of Worcester and Butler, but have, by their decision, attempted to overthrow that essential jurisdiction of the State. . . . I have, however, been prepared to meet this usurpation of Federal power with the most prompt and determined resistance, in whatever form its enforcement might have been attempted by any branch of the Federal Government.

After outlining plans for land lotteries of Cherokee and praising President Jackson’s support of his cause, he concluded by saying:

I have daily increased evidence that our policy has been founded in wisdom, justice and true benevolence, and will, ere long, terminate in the preservation of a remnant of these unfortunate Indians; and our State will be relieved from the libels and embarrassments of a thirty years controversy.

To make matters worse for Worcester and the Cherokees’ hopes, the Supreme Court adjourned for the rest of 1832 not long after releasing its decision, giving Lumpkin and Jackson nine months to resolve the matter before their inaction might warrant further Supreme Court action.

In the intervening months, the tide in the North turned against continued efforts on behalf of the Cherokee. Advocates and supportive congressmen came to the conclusion that federal action to protect them would exacerbate tensions around states’ rights and could split apart the Union. South Carolina’s leaders were already threatening secession, and they feared Georgia would join them, especially if the federal government intervened to protect the Cherokee. Thus, the tribe became a sacrifice to preserve the Union thirty years before the Civil War. Even the ABCFM, Worcester’s missionary society, gave up hope and counseled Cherokee leaders to negotiate a treaty and move west as the best option.

Just in case, Jackson’s Secretary of War, Lewis Cass, and Governor Lumpkin hatched a plan to ensure the case was taken care of prior the Supreme Court’s reconvening in 1833. Cass assured Lumpkin that the federal government wouldn’t stop until it obtained Cherokee land, so the governor pressed the legislature to repeal the law that lead to the missionaries’ arrest and agreed to pardon them if they dropped the case. With Worcester and Butler’s support evaporating and dashed hopes of the Supreme Court’s ruling mattering for Cherokee sovereignty, they dropped their case and were released. In total, they served 16 months in prison.

Worcester returned home to his family and continued his work at New Echota for two more years. Just like the Cherokees around them, a Georgia land lottery winner eventually claimed the Worcesters’ home and land. In 1835, the same year that his friend Elias Boudinot and others signed the Treaty of New Echota, the Worcesters moved to the western Cherokee land in Oklahoma, where they would live among the Cherokee for the rest of their lives. Samuel Worcester died in 1859 and is buried there.

Reflecting on this story, I was struck by the reality that Gilmer, Lumpkin, and Jackson all claimed to be Christians. Rather than stepping back to consider that their administrations were persecuting Christian U.S. citizens, they focused their ire on the encroaching power of the Supreme Court to dictate state decisions. Rather than viewing Cherokees as fellow human beings and neighbors, they assumed the supremacy of white Americans over the Cherokees, even to the point of arresting white missionaries who stood in their way. Their Christian faith was one of expediency and convenience—one that was advantageous to claim as long as it didn’t threaten their authority or wealth.

Now, in another sense, this story shouldn’t have shocked me. After all, we can’t remove this story from the broader context at that time. All three men owned plantations and countless slaves. Their administrations upheld an economy and culture built around slavery. In that era, a Christian abolitionist was viewed with more suspicion than a faithless slaveholder. Thus, their treatment of Worcester and the Cherokee people is more appropriately viewed as another offshoot of the same distorted gospel message that tolerated or even encouraged greed, while ignoring the dignity of fellow human beings.

During this imprisonment, Worcester wrote the following in a letter to his missionary society:3

It is a great happiness to be esteemed a deluded good man, rather than an ill-designing hypocrite. Let my name be sounded abroad as a weak, misguided enthusiast, yet a sincere lover of Jesus, anything consistent with sincere devotion to the cause of the Redeemer, rather told with the highest commendation man can bestow, and yet without the reputation of being a servant of Christ. Yet after all, it is a light thing to be judged of man’s judgment. We stand or fall at a higher tribunal.

Imagine what Georgia would be like today if its early leaders had held the faith of Worcester rather than the faith of Gilmer and Lumpkin.

This article of part two of a seven-part series on the Cherokee tribe’s expulsion from Georgia. In the next edition, we’ll dig into the story behind the unlikely timing of Georgia’s effort to memorialize New Echota and why it matters today. After that, we’ll circle back to Governors Lumpkin and Gilmer, among others, to reflect on how Georgia cities and counties got their names.

If you’ve benefited from reading this series, please consider forwarding it to your friends or sharing via social media. And, comment below with your reflections or questions.

In addition to the direct links within the article, the books below were used as reference:

Trail of Tears: The Rise and Fall of the Cherokee Nation - John Ehle

Unworthy Republic: The Dispossession of Native Americans and the Road to Indian Territory - Claudio Saunt

Jacksonland: President Andrew Jackson, Cherokee Chief John Ross, and the Great American Land Grab - Steve Inskeep

Letter from Samuel Worcester to Georgia Governor George Gilmer, June 10, 1831. Available at: https://www.wcu.edu/library/DigitalCollections/CherokeePhoenix/Vol4/no07/brainerd-cher-na-page-2-column-4a-page-3-column-1a.html

Letter to Missionary Society. Volume 27 (1831) of the Missionary Herald. p. 299-301 Accessed: https://earlyushistory.net/missionary-herald/

Letter from Samuel Worcester, November 8, 1831. Accessed in Volume 28 (1832) of the Missionary Herald. p. 19-20. Available at: https://earlyushistory.net/missionary-herald/

This is utterly fascinating. I found you via google as I researched these missionaries when I saw a reference to them as I taught the Trail of Tears to my children. It holds extra interest to me as a current American missionary who often finds myself in opposition to current US policy.

Thanks again, Sam, for this second part to your story. By this time, I resonate with your statement, “Rather than viewing Cherokees as fellow human beings and neighbors, they assumed the supremacy of white Americans over the Cherokees, even to the point of arresting white missionaries who stood in their way. Their Christian faith was one of expediency and convenience—one that was advantageous to claim as long as it didn’t threaten their authority or wealth. . . . Now, in another sense, THIS STORY SHOULDN’T HAVE SHOCKED ME. After all, we can’t remove this story from the broader context at that time. All three men owned plantations and countless slaves. . .” It’s so enlightening to read the actual quotes that incriminate the leaders for their hypocritical brand of Christianity as well as their cunning attempt to “change the subject” rather than enforce SCOTUS’ ruling. But, it’s mind-blowing to realize these facts of history were available but purposely NOT the ones that have been taught in our nation’s schools. It’s extremely important to allow our students to see & hear these different perspectives if they are to become activists for justice & good.